Earth’s groundwater supplies mapped for the first time

An international team of scientists has for the first time succeeded in producing the map of Earth's total groundwater supplies, Canadian University of Victoria announced on November 17, 2015. This pioneering attempt managed to provide significant information in the light of increasing global water demands. The next important step is to estimate how quickly we're depleting these supplies.

The scientists have first tried to estimate the global groundwater amounts during the 1970s. This attempt remained unsuccessful until now, when a group of hydrogeologists from the University of Victoria, the University of Calgary and the University of Göttingen produced data-driven estimate of the Earth's total supply of groundwater.

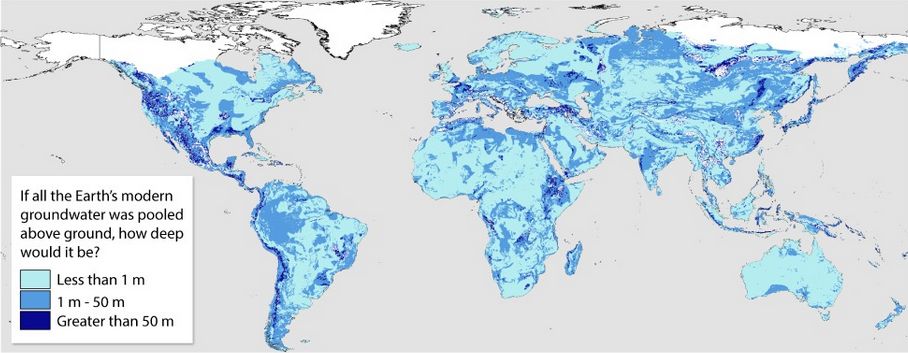

Image credit: Gleeson et al, 2015

Results of their research showed that less than 6% of groundwater in the upper 2 km (1.2 miles) of the Earth's landmass can be renewed during one human lifetime: "This has never been known before. We already know that water levels in lots of aquifers are dropping. We’re using our groundwater resources too fast – faster than they’re being renewed," said Dr. Tom Gleeson, leader of the research from the University of Victoria.

Groundwater is one of our most precious natural resources, and also one of the most exploited ones, perhaps, as it turns out, even more than any of us have been aware. The question of how much water is there still left, and how long do we have before our supplies run out, rapidly becomes one of our most significant questions, in the light of increasing global water demands.

Conducted study has provided important data to water managers and policy developers to aid in developing more sustainable ways of managing our groundwater resources.

Hydrogeologists have used numerous datasets, including data from almost a million watersheds, and more than 40 000 groundwater models to estimate a total volume of nearly 23 million cubic kilometers (5.5 million cubic miles) of total groundwater. Of this amount, about 0.35 million cubic kilometers (0.08 million cubic miles) is younger than 50 years old.

Young and old groundwater are fundamentally different in terms of interaction with the rest of the water and climate cycles. Older groundwater lies deeper and is often used as a water resource for agriculture and industry. It is, in general, saltier than ocean water, and can contain arsenic or uranium. In some areas, the briny water is so old, isolated and stagnant it should be thought of as non-renewable, according to Dr. Gleeson.

Younger groundwater supplies present a more renewable resource, as they are situated closer to surface water, and flow faster than old groundwaters. However, they are also more exposed to consequences of climate change and human contamination.

The produced map shows young groundwater supplies in tropical and mountain regions. Some of the largest deposits have been found in the Amazon Basin, the Congo, Indonesia, and in North and Central America running along the Rockies and the western Cordillera to the tip of South America.

High northern latitudes have not been included in the research as the data from satellite data doesn’t cover them accurately. Regardless, this area is largely under permafrost with little groundwater. The least amount of young groundwater supplies have been expected to be found in arid regions such as the Sahara, however it turned out this was not the case.

"Intuitively, we expect drier areas to have less modern groundwater and more humid areas to have more, but before this study, all we had was intuition. Now, we have a quantitative estimate that we compared to geochemical observations," explained Dr. Kevin Befus, who conducted the groundwater simulations at the University of Texas.

Next important research step will be to estimate how quickly we’re depleting groundwater supplies. Previously conducted studies have mapped global hot spots of groundwater stress, charting rates of precipitation compared to the rates of use through pumping, mostly for agriculture. Some of these hot spots are northern India and Pakistan, northern China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and parts of the US and Mexico.

"Since we now know how much groundwater is being depleted and how much there is, we will be able to estimate how long until we run out," Gleeson concluded.

Reference:

- "The global volume and distribution of modern groundwater" Tom Gleeson, Kevin M. Befus, Scott Jasechko, Elco Luijendijk, M. Bayani Cardenas – Nature Geoscience (2015) – doi:10.1038/ngeo2590

Featured image: How deep would water supplies be if all the Earth's modern water was pooled above ground. Image credit: Gleeson et al, 2015.

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules:

We reserve the right to remove any comments that violate these rules. By commenting on our website, you agree to abide by these guidelines. Thank you for helping to create a positive and welcoming environment for all.