Swarm of strong earthquakes hits Cook Strait, New Zealand – M 6.5 strongest so far

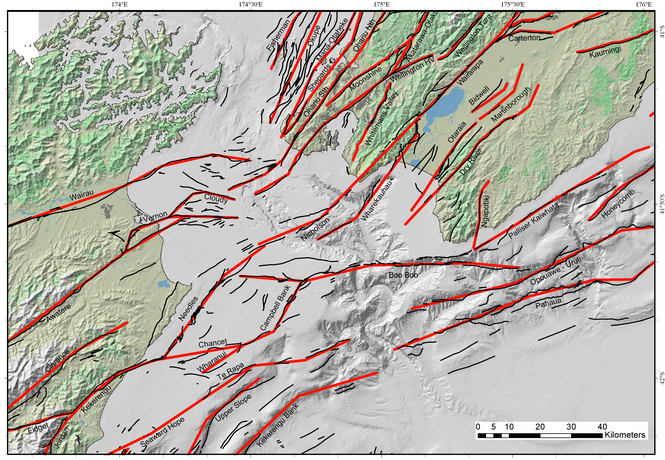

After series of strong foreshocks, a very strong and shallow M6.5 earthquake hit Cook Strait, New Zealand at 05:09 UTC on Sunday, July 21, 2013. USGS reported a depth of 14 km (8.7 miles). The epicenter was located 46 km (29 miles) ESE of Blenheim and 54 km (34 miles) SSW of Wellington.

GDACS estimates there are 43 000 people living within 100 km (62 miles) radius. No tsunami warning was issued.

Damage was reported in capital Wellington which also suffered a loss of power. One minor injury was reported so far.

ER writes that one of the main dangers for this earthquake are landslides, mainly in the Wellington area. As people are reporting 30 seconds of shaking, the risk is even bigger than before. The longer shaking lasts, the more chance on damage and landslides.

Civil Defence is warning people to stay out of Wellington CBD (Central Business District) because of the risk of falling debris.

As New Zealand is heading into night the area is still shaking and stronger earthquakes are not excluded.

GNS Science estimates that in the coming week there could be up to nine magnitude 5.0 or greater events, with an approximately 30% probability (a 1 in 3 chance) of a magnitude 6.0 or greater. The most likely period for this to occur is the next 24 hours, when the probability is approximately 20% (a 1 in 5 chance).

An offshore earthquake needs to be at least magnitude 7.5 for a tsunami to be considered possible. The 1855 magnitude 8.2 Wairarapa earthquake is New Zealand's most severe quake since European colonisation, which produced a tsunami with a maximum height of 10-11m at Palliser Bay. The tsunami also inundated Lambton Quay, where it reached a height of 2.4m. GEONET

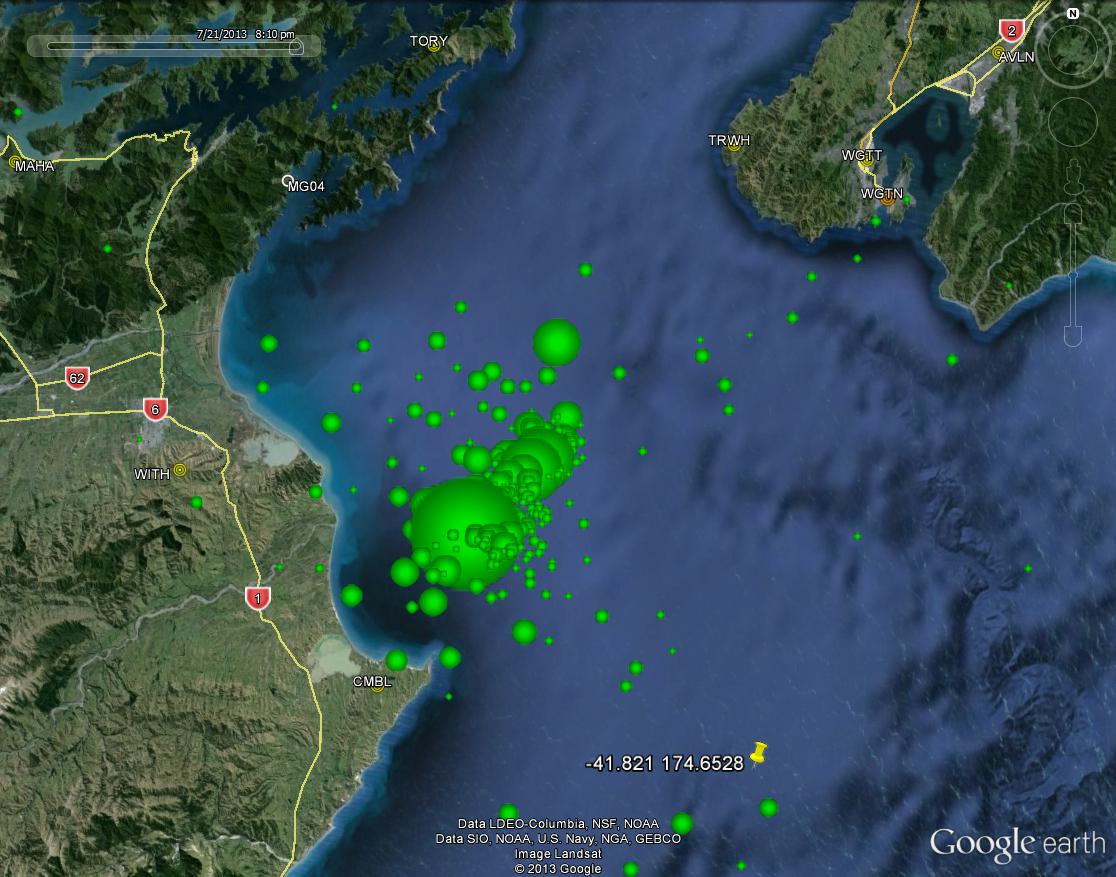

A map showing epicentres of the Cook Strait earthquakes, with the spheres sized according to their magnitude. Credit: GeoNet

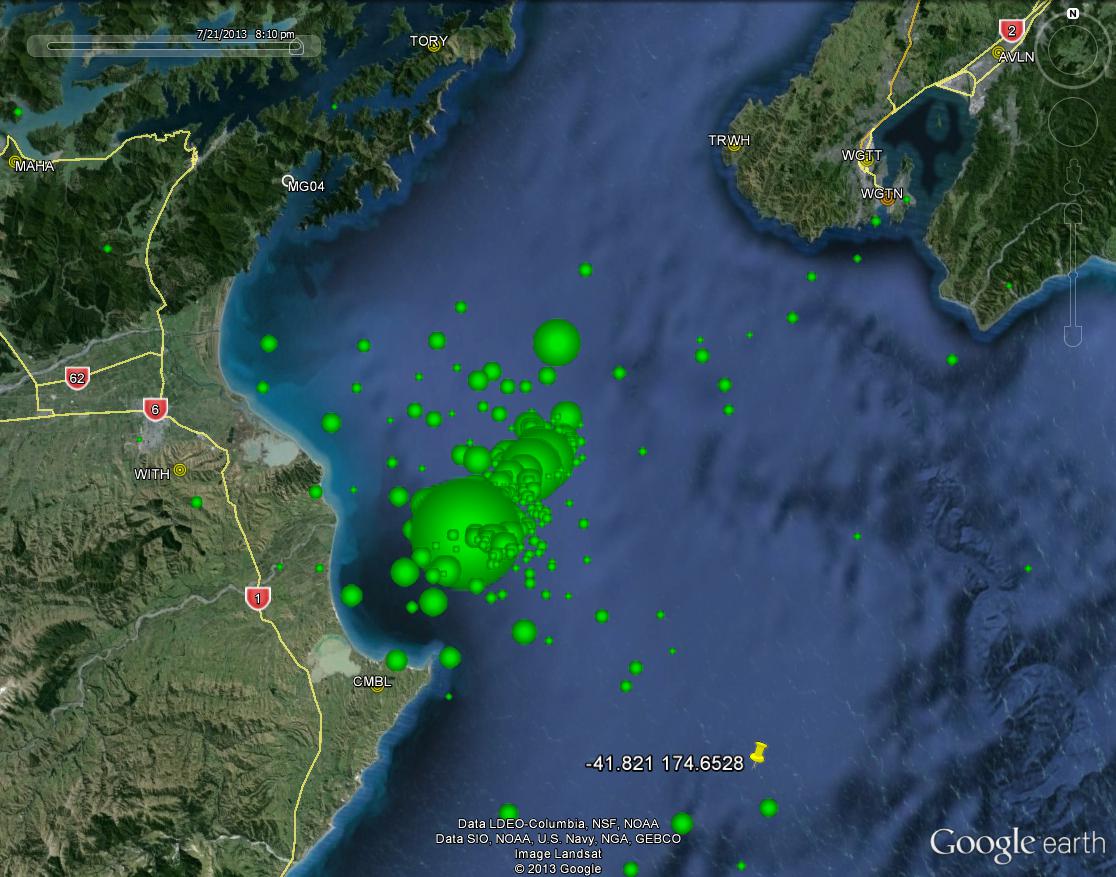

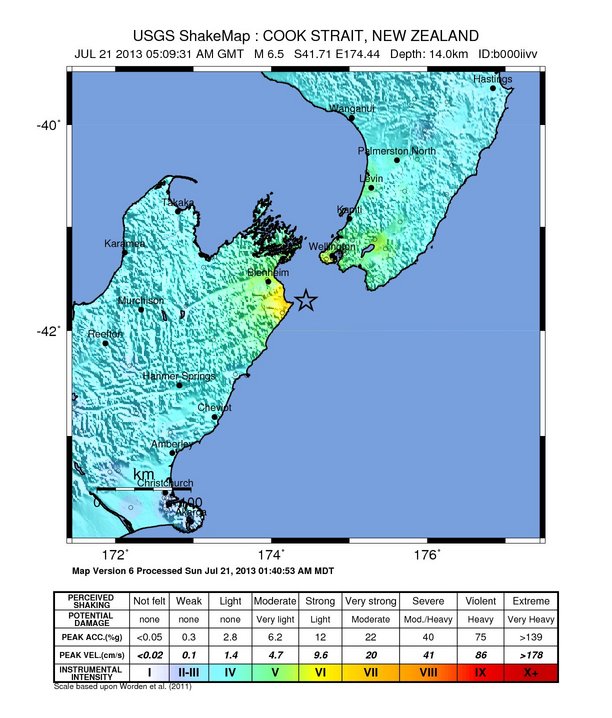

Active faults and earthquake sources in the Cook Strait

The country sits astride two moving segments of the planet's surface – the Pacific and Australian tectonic plates. New Zealand is riddled with faults created by the collision of these plates. Some faults are just on land, some are under the sea, and others straddle land and sea.

The plates are continually moving. This can cause a fault to rupture, triggering an earthquake and associated hazards. The coast of New Zealand is largely surrounded by active faults capable of triggering large-magnitude earthquakes.

New Zealand faces a variety of hazards associated with undersea geological activity and the main hazards as explained by NIWA are:

- earthquakes

- submarine landslides and associated tsunami

- volcanic eruptions

- seafloor scour, sediment transport, and shallow gas.

Active faults and earthquake sources in the Cook Strait Credit: NIWA

Tectonic summary of today's M 6.5

Today's Mw 6.5 earthquake occurred as a result of oblique thrust faulting on or near the plate boundary between the Pacific and Australia plates. At the latitude of this earthquake, the Pacific plate is converging with Australia, moving westward at a rate of approximately 43 mm/yr, and is beginning a complex transition from Pacific plate subduction along the Hikurangi Trench to the north, to transform faulting along the Alpine Fault system and its associated structures to the south west. The depth and faulting mechanism of this earthquake are consistent with this tectonic transition.

The July 21 earthquake is the latest in a sequence of moderate earthquakes in the same region over the preceding two days, which began on July 18 2013 with a M 5.3 event approximately 25 km to the northwest, and continued with a M 5.8 event on July 20, just to the northeast of the July 21 earthquake. A number of smaller shocks occurred in the same area over the intervening period, and several dozen aftershocks of M<5 had been recorded by the New Zealand national network, GeoNet, within 2 hours of the mainshock. Many of these earthquakes align on an approximate NE-SW trend between the North and South Islands of New Zealand. Historically, this region has hosted several large earthquakes, including the M 7.5 1848 Marlborough event a few tens of kilometers to the northwest of the July 21 earthquake, and the M 8.2 1855 Wairarapa event, some 80 km to the northeast.

Seismotectonics of the Eastern Margin of the Australia Plate

The eastern margin of the Australia plate is one of the most sesimically active areas of the world due to high rates of convergence between the Australia and Pacific plates. In the region of New Zealand, the 3000 km long Australia-Pacific plate boundary extends from south of Macquarie Island to the southern Kermadec Island chain. It includes an oceanic transform (the Macquarie Ridge), two oppositely verging subduction zones (Puysegur and Hikurangi), and a transpressive continental transform, the Alpine Fault through South Island, New Zealand.

Since 1900 there have been 15 M7.5+ earthquakes recorded near New Zealand. Nine of these, and the four largest, occurred along or near the Macquarie Ridge, including the 1989 M8.2 event on the ridge itself, and the 2004 M8.1 event 200 km to the west of the plate boundary, reflecting intraplate deformation. The largest recorded earthquake in New Zealand itself was the 1931 M7.8 Hawke's Bay earthquake, which killed 256 people. The last M7.5+ earthquake along the Alpine Fault was 170 years ago; studies of the faults' strain accumulation suggest that similar events are likely to occur again.

North of New Zealand, the Australia-Pacific boundary stretches east of Tonga and Fiji to 250 km south of Samoa. For 2,200 km the trench is approximately linear, and includes two segments where old (>120 Myr) Pacific oceanic lithosphere rapidly subducts westward (Kermadec and Tonga). At the northern end of the Tonga trench, the boundary curves sharply westward and changes along a 700 km-long segment from trench-normal subduction, to oblique subduction, to a left lateral transform-like structure.

Australia-Pacific convergence rates increase northward from 60 mm/yr at the southern Kermadec trench to 90 mm/yr at the northern Tonga trench; however, significant back arc extension (or equivalently, slab rollback) causes the consumption rate of subducting Pacific lithosphere to be much faster. The spreading rate in the Havre trough, west of the Kermadec trench, increases northward from 8 to 20 mm/yr. The southern tip of this spreading center is propagating into the North Island of New Zealand, rifting it apart. In the southern Lau Basin, west of the Tonga trench, the spreading rate increases northward from 60 to 90 mm/yr, and in the northern Lau Basin, multiple spreading centers result in an extension rate as high as 160 mm/yr. The overall subduction velocity of the Pacific plate is the vector sum of Australia-Pacific velocity and back arc spreading velocity: thus it increases northward along the Kermadec trench from 70 to 100 mm/yr, and along the Tonga trench from 150 to 240 mm/yr.

The Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone generates many large earthquakes on the interface between the descending Pacific and overriding Australia plates, within the two plates themselves and, less frequently, near the outer rise of the Pacific plate east of the trench. Since 1900, 40 M7.5+ earthquakes have been recorded, mostly north of 30°S. However, it is unclear whether any of the few historic M8+ events that have occurred close to the plate boundary were underthrusting events on the plate interface, or were intraplate earthquakes. On September 29, 2009, one of the largest normal fault (outer rise) earthquakes ever recorded (M8.1) occurred south of Samoa, 40 km east of the Tonga trench, generating a tsunami that killed at least 180 people.

Across the North Fiji Basin and to the west of the Vanuatu Islands, the Australia plate again subducts eastwards beneath the Pacific, at the North New Hebrides trench. At the southern end of this trench, east of the Loyalty Islands, the plate boundary curves east into an oceanic transform-like structure analogous to the one north of Tonga.

Australia-Pacific convergence rates increase northward from 80 to 90 mm/yr along the North New Hebrides trench, but the Australia plate consumption rate is increased by extension in the back arc and in the North Fiji Basin. Back arc spreading occurs at a rate of 50 mm/yr along most of the subduction zone, except near ~15°S, where the D'Entrecasteaux ridge intersects the trench and causes localized compression of 50 mm/yr in the back arc. Therefore, the Australia plate subduction velocity ranges from 120 mm/yr at the southern end of the North New Hebrides trench, to 40 mm/yr at the D'Entrecasteaux ridge-trench intersection, to 170 mm/yr at the northern end of the trench.

Large earthquakes are common along the North New Hebrides trench and have mechanisms associated with subduction tectonics, though occasional strike slip earthquakes occur near the subduction of the D'Entrecasteaux ridge. Within the subduction zone 34 M7.5+ earthquakes have been recorded since 1900. On October 7, 2009, a large interplate thrust fault earthquake (M7.6) in the northern North New Hebrides subduction zone was followed 15 minutes later by an even larger interplate event (M7.8) 60 km to the north. It is likely that the first event triggered the second of the so-called earthquake "doublet".

More information on regional seismicity and tectonics

Featured image: USGS

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules:

We reserve the right to remove any comments that violate these rules. By commenting on our website, you agree to abide by these guidelines. Thank you for helping to create a positive and welcoming environment for all.