Ecuador’s Tungurahua volcano spews red-hot rocks, billows ash with pyroclastic flow

The Tungurahua volcano in Ecuador is spewing out red-hot rocks and billowing coarse ash with pyroclastic flows. The South American country’s Geophysical Institute – IGEPN says the increased activity began Sunday afternoon. It says the volcano has thrown pyroclastic boulders up to a mile from the crater, and there have been at least four earthquakes in the area.

Photograph showing the Tungurahua volcano ash emission column about 3 km altitude and heading east. taken at 05:50 of November 28, 2011(Credit: G. Viracucha)

Photograph showing the Tungurahua volcano ash emission column about 3 km altitude and heading east. taken at 05:50 of November 28, 2011(Credit: G. Viracucha) The volcano’s seismic activity remains at a high level. There was an explosion that led to the expulsion of hot material that covered all sides of the volcano and the generation of a pyroclastic flow that descended the gorge Achupashal. There is the constant presence of a column of ash emission, which reaches an average height of 3 km and goes to the east and southeast.

On Nov 27 the Tungurahua volcano showed a rapid process eruption accompanied by explosions, pyroclastic flows, block release incandescent and falling ash and gravel, which mainly affected the western flank of the volcano. Pyroclastic streams descending the Achupashal, Chotanpamba and Mandur in the northwestern flank of the volcano and western flank.

The volcano watchers reported also the occurrence of heavy gunfire and explosions caused by like sounds of falling rocks. There are reports of ash fall in the towns of Bilbao and Manzano. So far the volcano keeps intense seismic activity. This process occurred while the volcano eruption showed a level of activity considered as moderate to low, characterized by small fumaroles in the crater and a small number of volcanic earthquakes. The Geophysical Institute will continue to closely monitor the activity of this volcano.

Tungurahua Volcano webcam – View from the Southwest (Bayushig)

Recentry awaken Colombian volcano Galeras is 321 kilometres (200 miles) from Tungurahua.

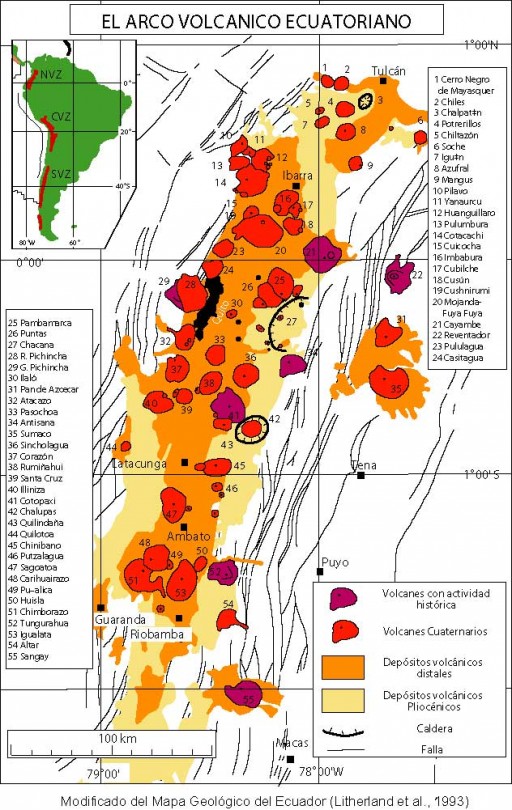

Geodynamic context

The Ecuadorian volcanic arc is part of the Northern Volcanic Zone of the Andes (NVZ), which extends from 5 ° N (Cerro Bravo volcano in Colombia) to 2 ° S (Sangay volcano, Ecuador) (Barberi et al ., 1988). South of Sangay there are no active volcanoes in the Andes to the region of Arequipa, Peru.

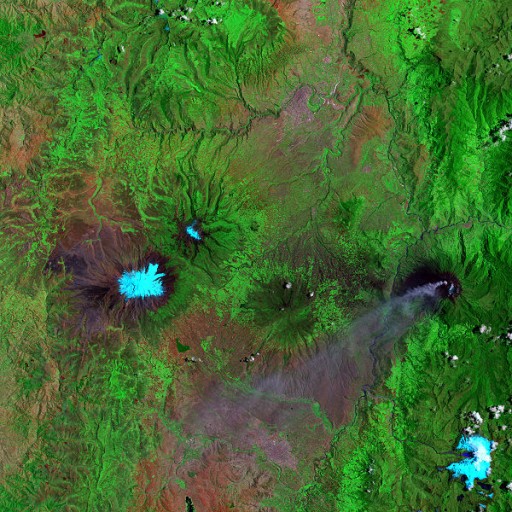

False-color satellite image of Chimborazo (center, left), Carihuairazo (10km northeast of Chimborazo), Tungurahua (center, right with ash plume) and El Altar (bottom, right), Ecuador. Pale blue indicates snow/ice cover, bright green indicates lush vegetation, and red indicates sparser vegetation. Tungurahua’s volcanic ash plume appears in lavender. Image width is 78km, image direction is top to North. (Credit: Jesse Allen, NASA Earth Observatory, based on data provided by the Landsat 7 science team and the University of Maryland’s Global Land Cover Facility.)

False-color satellite image of Chimborazo (center, left), Carihuairazo (10km northeast of Chimborazo), Tungurahua (center, right with ash plume) and El Altar (bottom, right), Ecuador. Pale blue indicates snow/ice cover, bright green indicates lush vegetation, and red indicates sparser vegetation. Tungurahua’s volcanic ash plume appears in lavender. Image width is 78km, image direction is top to North. (Credit: Jesse Allen, NASA Earth Observatory, based on data provided by the Landsat 7 science team and the University of Maryland’s Global Land Cover Facility.) The volcanism in the Ecuadorian Andes is the result of the subduction of the Nazca oceanic plate beneath the continental plate of South America. The Nazca oceanic plate is aged between 12 and 20 million years (Ma) off the coast of Ecuador and includes the Carnegie submarine ridges. This ridge of volcanic origin, is the product of the activity of the Galapagos hotspot on the Nazca plate.

The Ecuadorian volcanic arc is characterized by very wide (100-120 km) and present several parallel rows of volcanoes, what differentiates Colombia volcanic arc (30-50 km wide), which consists of a single row of volcanoes. Ecuador Volcanoes can be classified in two ways: the first classification is according to Hall and Beate (1991), who defined four rows according to the type of base / substrate underlying the volcanoes: Western Cordillera, the valleys, the Cordillera Real and the East. In contrast, the second corresponds to Monzier et al. (1999), who based on geochemistry grouped in three rows of volcanoes NNE (the volcanic front, the main volcanic arc and the After-arc), and Riobamba volcanoes that form the southern end of the bow in Ecuador. In this grouping geochemical Main Arc includes volcanoes over the Inter-Andean Valley of the Cordillera Real, while the separation of Riobamba volcanoes is performed based on their geochemical variability restricted (basic andesite andesites) with the rest arc. (IGEPN)

The Ecuadorian volcanic arc is part of the Northern Volcanic Zone of the Andes (NVZ), which extends from 5 ° N (Cerro Bravo volcano in Colombia) to 2 ° S (Sangay volcano, Ecuador) (Barberi et al ., 1988). South of Sangay there are no active volcanoes in the Andes to the region of Arequipa, Peru.

The Ecuadorian volcanic arc is part of the Northern Volcanic Zone of the Andes (NVZ), which extends from 5 ° N (Cerro Bravo volcano in Colombia) to 2 ° S (Sangay volcano, Ecuador) (Barberi et al ., 1988). South of Sangay there are no active volcanoes in the Andes to the region of Arequipa, Peru. Tungurahua volcano

Tungurahua is a steep-sided stratovolcano with an almost perfect cone reaching 5,023-meter (16,480-foot) in the Eastern Cordillera of the Andes. Its geographical location is 1.467°S and 78.442°W, 15 km east of Ambato, Ecuador’s fourth largest city and capital of the province of the same name as the volcano. The steep flanks of the volcano are used for agriculture and many small villages and a larger town, called Baños cradle the mountain on the northern and western side, which were affected in various degrees by lahar and ashes in the last few years. It has been active since 1999.

Strombolian-style eruption of Tungurahua Volcano, Ecuador on Nov 2 1999 (Credit: USGS)

Strombolian-style eruption of Tungurahua Volcano, Ecuador on Nov 2 1999 (Credit: USGS) The volcano emits continuously ashes, smoke and lava (Strombolian activity). Magma rises up the chimney and reaches the opening of the volcano. The danger of a big eruption lies in the blockage of the exit vent by big boulders and other materials. If it cannot exit freely anymore, there is a chance that more and more pressure accumulates under the blockage and finally leads to a huge explosion with potential structural collapse. Should that happen and the peak should break away, then a huge catastrophe is at hand as Baños and the other surrounding villages will be completely destroyed and some 20 000 people are in danger of losing their lives.

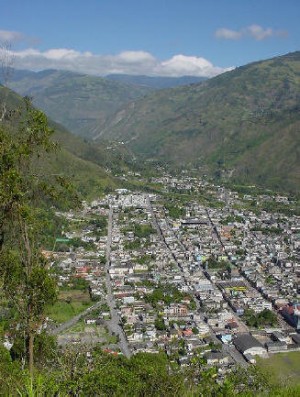

Baños, a tourist town of several thousand inhabitants, lies to the north at the foot of Tungurahua and is in a high danger zone as it sits in a narrow valley with no ways of escape for the population in the event of a big eruption. The volcano has almost 3000m of steep vertical slopes, which ensures rapid descents of pyroclastic flows and lahars, which would reach the town within minutes. The damages until now were mostly restricted by the continuous fallout of ashes, affecting pastures and crops and combined with heavy rains producing mudslides blocking roads.

Baños, a tourist town of several thousand inhabitants, lies to the north at the foot of Tungurahua and is in a high danger zone as it sits in a narrow valley with no ways of escape for the population in the event of a big eruption. The volcano has almost 3000m of steep vertical slopes, which ensures rapid descents of pyroclastic flows and lahars, which would reach the town within minutes. The damages until now were mostly restricted by the continuous fallout of ashes, affecting pastures and crops and combined with heavy rains producing mudslides blocking roads. Historical eruptions have originated from the summit crater and have included strong explosions and sometimes lava flows, lahars and pyroclastic eruptions that reached populated areas at its base. The volcano’s complex historical record includes sudden and violent eruptions with the potential of sector collapses on top. When the volcano increased its activity in 1999, the ice cap melted away and the peak is since then ice free.

In the middle of October 1999, when the danger level was raised from yellow to orange alert, the government started to evacuate the people living in the vicinity of the volcano. More then 20 000 persons, including all the inhabitants of Baños, a tourist town located at the foot of the colossus, were moved to shelters in nearby larger cities, in particular to Ambato, the capital of the province. All roads leading to the vicinity of Tungurahua were closed and patrolled by the military. That interrupted a major access to the Amazon like the Ambato – Puyo highway.

Baños appeared to be a ghost town with no apparent life although a few people stayed back, hidden away in the church and their houses. Others also bypassed the military controls to tend to their farms and many more began to clamor soon for a return to their homes and businesses. Then, just before Christmas of 1999, the tensions came to a violent conclusion as protesters confronted the military, claiming one life in the clashes. After those events the authorities let the people return at their own risk although nothing really changed yet in the danger.

Lahars almost completely destroyed the highway leading from Baños to Riobamba. Constant accumulations of ashes occur on the steep western flank of the volcano as the wind almost always blows from the east. Combined with heavy rains they form devastating mudslides, destroying bridges and the road. Photo to the right shows a makeshift bridge. In the above picture an old lava flow can be observed in the exposed rock wall near Rio Verde, located some 20 km down the Pastaza valley. Vertical rock formation change drastically to horizontal one, representing the lava flow of an ancient big eruption of Tungurahua volcano. (Ecuador-Travel)

[…] of residents and tourists. Tungurahua daily report from November 30 issued by IGEPNRead our last article about Tungurahua with information about geodynamic context and volcano […]