Venus transit of 2012 will not be seen again until 2117

A transit of Venus is the observed passage of the planet across the disk of the Sun. The planet Venus, orbiting the Sun “on the inside track,” catches up to and passes the slower Earth. Venus, appearing as a small dot in the foreground, will move from left to right across the Sun. The word “transit” means passage or movement—in this case, across the face of the Sun.

The transit or passage of a planet across the disk of the Sun may be thought of as a special kind of eclipse. As seen from Earth, only transits of the inner planets Mercury and Venus are possible. Planetary transits are far more rare than eclipses of the Sun by the Moon. On the average, there are 13 transits of Mercury each century. In comparison, transits of Venus usually occur in pairs with eight years separating the two events. However, more than a century elapses between each transit pair. The first transit ever observed was of the planet Mercury in 1631 by the French astronomer Gassendi. A transit of Venus occurred just one month later but Gassendi’s attempt to observe it failed because the transit was not visible from Europe. In 1639, Jerimiah Horrocks and William Crabtree became the first to witness a transit of Venus.

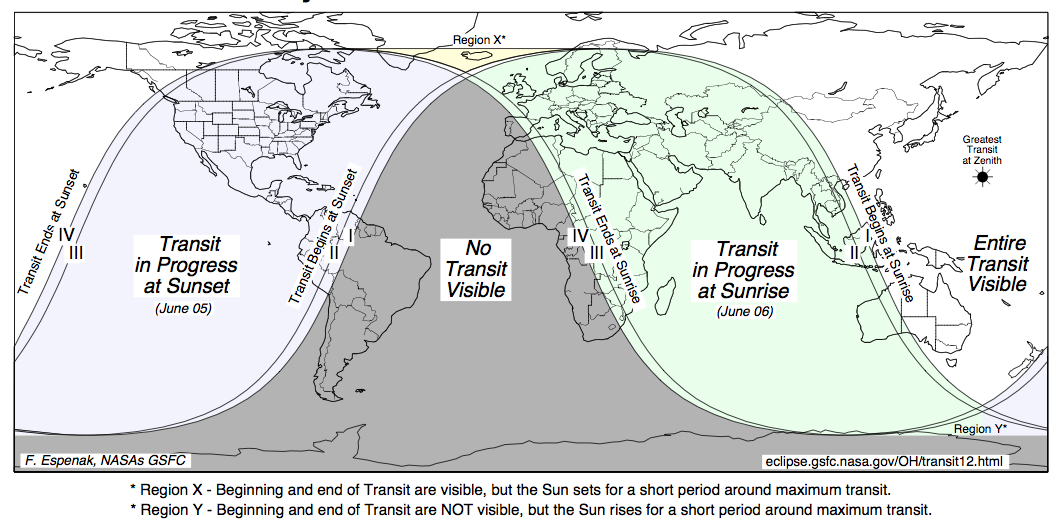

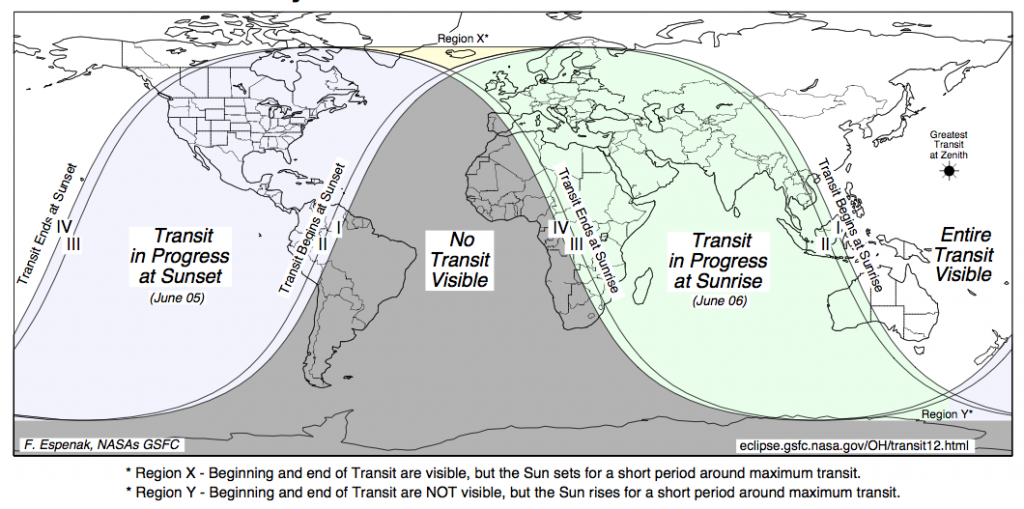

The next transit of Venus will occur on June 6th (Tuesday, June 5th from the Western Hemisphere) in 2012. The entire event of 2012 will be widely visible from the western Pacific, eastern Asia and eastern Australia. Most of North and Central America, and northern South America will witness the beginning of the transit (on June 5) but the Sun will set before the event ends. Similarly, observers in Europe, western and central Asia, eastern Africa and western Australia will see the end of the event since the transit will already be in progress at sunrise from those locations.

After 2012, the next transits of Venus will be in December 2117 and December 2125.

Why is a transit of Venus so rare?

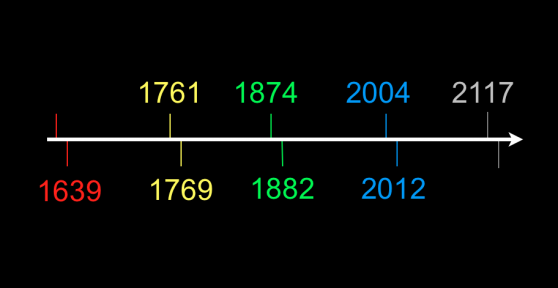

Transits of Venus have a strange pattern of frequency. A transit will not have happened for about 121 ½ years (prior to 2004, the last one was 1882). Then there will be one transit (such as the one in 2004) followed by another transit of Venus eight years later (in the year 2012). Then there will be a span of about 105 ½ years before the next pair of transits occur, again separated by eight years. Then the pattern repeats (121 ½ , 8, 105 ½ , 8).

If Venus and the earth orbited the Sun in the same plane as the sun, transits would happen frequently. However, the orbit of Venus is inclined to the orbit of earth, so when Venus passes between the Sun and the Earth every 1.6 years, Venus usually is a little bit above or a little bit below the sun, invisible in the Sun’s glare.

A similar thing happens with our Moon. Every month the Moon passes between the Sun and the Earth, yet we do not see a solar eclipse every month. That’s because the moon’s orbit is also slightly inclined to Earth’s orbit, so the new moon is usually a little above or a little below the sun. The transit of Venus is essentially an annular eclipse of the Sun by Venus.

See the paper plate activity at analyzer.depaul.edu for a model that shows the transit frequency visually.

Because Venus’s orbit is considerably larger than Mercury’s orbit, transits of Venus are much rarer. Indeed, only six such events have occurred since the invention of the telescope (1631,1639, 1761,1769, 1874 and 1882). Transits of Venus are only possible during early December and June when Venus’s orbital nodes pass across the Sun. Transits of Venus show a clear pattern of recurrence at intervals of 8, 121.5, 8 and 105.5 years. The following table lists all transits of Venus during the 800 year period from 1601 through 2400.

Transits of Venus: 1601-2400

Date Universal Separation

Time (Sun and Venus)

1631 Dec 07 05:19 940"

1639 Dec 04 18:25 522"

1761 Jun 06 05:19 573"

1769 Jun 03 22:25 608"

1874 Dec 09 04:05 832"

1882 Dec 06 17:06 634"

2004 Jun 08 08:19 627"

2012 Jun 06 01:28 553"

2117 Dec 11 02:48 724"

2125 Dec 08 16:01 733"

2247 Jun 11 11:30 693"

2255 Jun 09 04:36 492"

2360 Dec 13 01:40 628"

2368 Dec 10 14:43 835"

Transit of Venus 2012 – June 05/06

The 2012 transit of Venus will be visible from North America, the Pacific, Asia, Australia, eastern Europe, and eastern Africa. More details can be found at 2012 Transit of Venus.

It can be safely observed by taking the same precautions used when observing the partial phases of a solar eclipse. Staring at the brilliant disk of the Sun with the unprotected eye can quickly cause serious and often permanent eye damage.

To determine whether a transit of Venus is visible from a specific geographic location, it is simply a matter of calculating the Sun’s altitude and azimuth during each phase of the transit using information tabulated in the Six Millennium Catalog of Venus Transits.

Click to access and enlarge PDF version of map showing visibility of 2012 transit of Venus. Courtesy of Fred Espenak (NASA GSFC), who provides additional transit of Venus data from NASA.

For Northern Hemisphere locations above latitude ~67° north, all of the transit is visible regardless of the longitude. Northern Canada and all of Alaska will also see the entire event. Residents of Iceland are in a unique wedge-shaped part of the path. They will see both the start and end of the transit but the Sun will set for a short period around greatest transit. A similarly shaped region exists south of Australia, but here, the Sun rises after the transit begins and sets before the event ends.

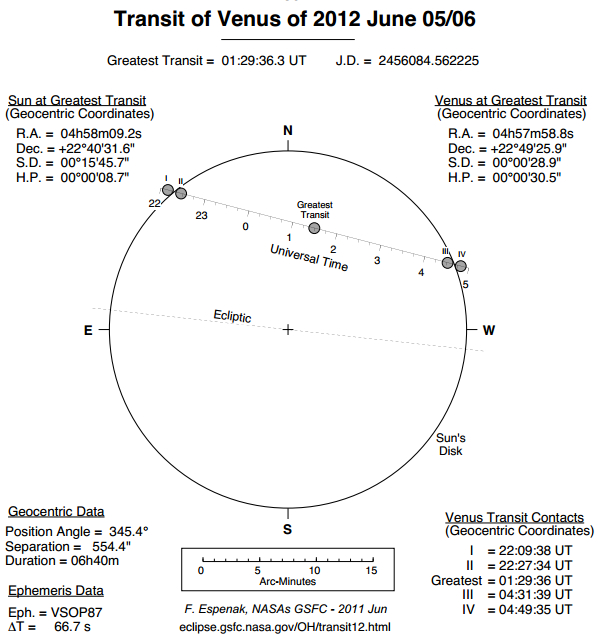

The principal events occurring during a transit are conveniently characterized by contacts, analogous to the contacts of an annular solar eclipse. The transit begins with contact 1, the instant the planet’s disk is externally tangent to the Sun. Shortly after contact I, the planet can be seen as a small notch along the solar limb. The entire disk of the planet is first seen at contact 2 when the planet is internally tangent to the Sun. Over the course of several hours, the silhouetted planet slowly traverses the solar disk. At contact 3, the planet reaches the opposite limb and once again is internally tangent to the Sun. Finally, the transit ends at contact 4 when the planet’s limb is externally tangent to the Sun. Contacts 1 and 2 define the phase called ingress while contacts 3 and 4 are known as egress. Position angles for Venus at each contact are measured counterclockwise from the north point on the Sun’s disk.

During the 2012 transit, Venus’s minimum separation from the Sun is 554 arc-seconds (During the 2004 transit, the minimum separation was 627 arc-seconds). The position angle is defined as the direction of Venus with respect to the center of the Sun’s disk, measured counterclockwise from the celestial north point on the Sun. Figure 2 shows the path of Venus across the Sun’s disk and the scale gives the Universal Time of Venus’s position at any point during the transit. The celestial coordinates of the Sun and Venus are provided at greatest transit as well as the times of the major contacts.

Note that these times are for an observer at Earth’s center. The actual contact times for any given observer may differ by up to ±7 minutes. This is due to effects of parallax since Venus’s 58 arc-second diameter disk may be shifted up to 30 arc-seconds from its geocentric coordinates depending on the observer’s exact position on Earth.

The diagram shows the path of Venus across the sun and the contact times from an earth-centered perspective. However, from different locations on earth, the exact contact times vary by minutes or seconds. That slight difference in times is the essence of a transit’s value, for it allowed astronomers to calculate the size of the solar system.

The entire event takes about 6 hours 40 minutes. The times in the diagram are in Universal Time, or essentially Greenwich Time.

For simplicity, visit transitofvenus.nl/details.html, or transitofvenus.nl/wp/where-when/local-transit-times/.

Ancient and medieval history

Ancient Indian, Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian and Chinese observers knew of Venus and recorded the planet’s motions. The early Greeks thought that the evening and morning appearances of Venus represented two different objects—Hesperus the evening star and Phosphorus the morning star. Pythagoras is credited with realizing they were the same planet. There is no evidence that any of these cultures knew of the transits.

Venus was important to ancient American civilizations, in particular for the Maya, who called it Noh Ek, “the Great Star” or Xux Ek, “the Wasp Star“; they embodied Venus in the form of the god Kukulkán also known as or related to Gukumatz and Quetzalcoatl in other parts of Mexico). In the Dresden Codex, the Maya charted Venus’ full cycle, but despite their precise knowledge of its course, there is no mention of the transit.

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules:

We reserve the right to remove any comments that violate these rules. By commenting on our website, you agree to abide by these guidelines. Thank you for helping to create a positive and welcoming environment for all.