Observing 2012 Geminid meteor shower

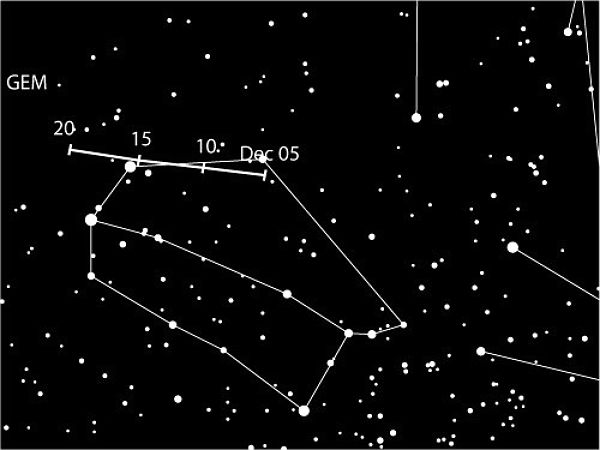

Observing at the Northern Hemisphere started as early as December 6, when one meteor every hour or so could be visible. During the next week, rates increase until a peak of 50-80 meteors per hour is attained on the night of December 12/13. By December 18 meteor shower disappears in the vast space.

Luckily, the Moon will be absent when the Geminids are at their peak on the evening of December 12/13.

The following charts will help you find Geminids from both hemispheres:

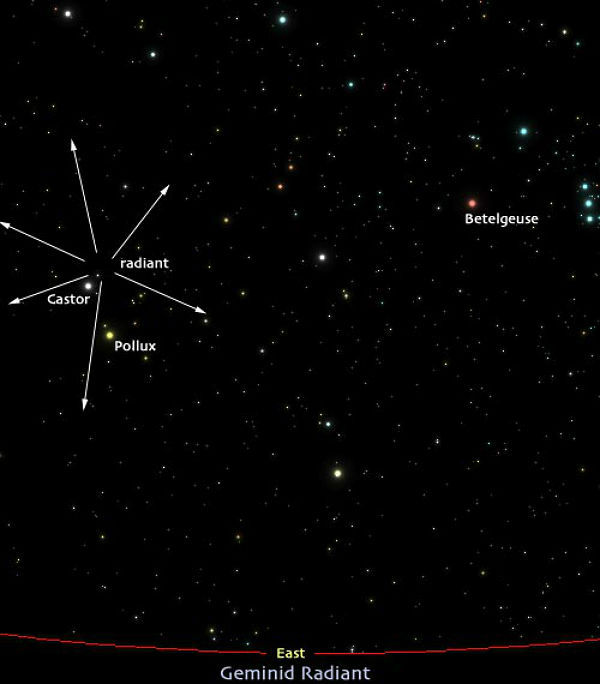

Location of the Geminids for Northern Hemisphere observers. The view from mid-northern latitudes around December 13. The graphic does not represent the view at the time of maximum, but is simply meant to help prospective observers to find the radiant location. The red line across the bottom of the image represents the horizon. (Source: Meteor Showers Online)

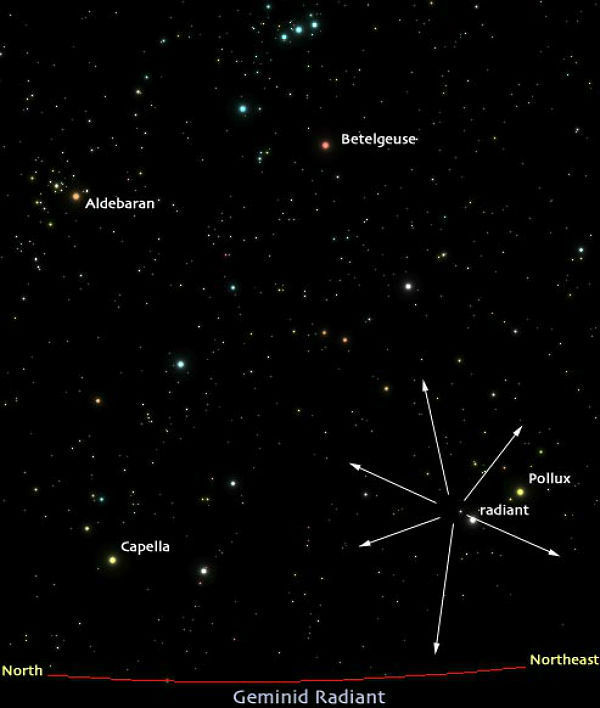

Location of the Geminids for Northern Hemisphere observers. The view from mid-northern latitudes around December 13. The graphic does not represent the view at the time of maximum, but is simply meant to help prospective observers to find the radiant location. The red line across the bottom of the image represents the horizon. (Source: Meteor Showers Online)  Location of the Geminids for Southern Hemisphere observers. The view from mid-southern latitudes around December 13. The graphic does not represent the view at the time of maximum, but is simply meant to help prospective observers to find the radiant location. The red line across the bottom of the image represents the horizon. Although the actual radiant is below the horizon, the stars just above the horizon are those of the constellation Perseus. (Source: Meteor Showers Online)

Location of the Geminids for Southern Hemisphere observers. The view from mid-southern latitudes around December 13. The graphic does not represent the view at the time of maximum, but is simply meant to help prospective observers to find the radiant location. The red line across the bottom of the image represents the horizon. Although the actual radiant is below the horizon, the stars just above the horizon are those of the constellation Perseus. (Source: Meteor Showers Online)

More weaker meteor showers going on around the same time as the Geminids – Delta Arietids (December 8-January 2), Canis Minorids (December 4-15), Coma Berenicids (December 8-January 23), Sigma Hydrids (December 4-15), December Monocerotids (November 9-December 18), Northern Chi Orionids (November 16-December 16), Southern Chi Orionids (December 2-18), Phoenicids (November 29-December 9), Ursids (December 17 – December 26) and Alpha Puppids (November 17-December 9).

(Credit: International Meteor Organization)

(Credit: International Meteor Organization)

According to Margaret Campbell-Brown and Peter Brown in the Observer’s Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, the Geminids are predicted to reach peak activity at 8 p.m. EST Dec. 13 (00:00 UT on Dec. 14). That means those in Europe and North Africa east to central Russia and China are in the best position to catch the very crest of the shower, when the rates conceivably could exceed 120 meteors per hour!

“Meteor Counter” app

Phaeton mystery

The parent object of the Geminids, known as Phaethon, is very mysterious because it is not a comet, but a minor planet. Most of the major meteor showers have well-known comets associated with them and these comets help to replenish the meteors as they shed their dust and gas when close to the sun. There is no evidence that minor planets shed any of their material, so the actual replenishment of dust in the orbit of the Geminid meteor stream has been a mystery.

There is a curious consistency to the annual Geminid display that could only be explained by assuming something was still dumping dust into its orbit. After observing Phaeton passing through the field of the STEREO-A spacecraft during the period of June 17-22, 2009 researchers noted an unexpected brightening, which was due to dust being released. Phaethon was “too hot for water ice to survive, rendering unlikely the possibility that dust is ejected” in the same fashion as a comet. They concluded that the dust was released as a result of the sun overheating the minor planet, which caused rock on the surface to fracture. If just ten such events occurred each time Phaethon passed close to the sun, enough dust would be released to sustain the Geminids. Further observations will be needed to determine if this was a one-time event or not, but, for now, this is the best theory to explain what keeps the Geminids going.

Sources: Meteor Showers Online, International Meteor Organization, Meteorwatch.org

Featured image: screen capture from video Look Up!

[…] Observing 2012 Geminid meteor shower. Share this:TwitterFacebookLinkedInTumblrMoreEmailPrintGoogle +1DiggRedditPinterestStumbleUponLike this:LikeBe the first to like this. […]