Telescope image shows star formation can be a violent and explosive process

Stellar explosions are most often associated with supernovae, the spectacular deaths of stars. But new ALMA observations provide insights into explosions at the other end of the stellar life cycle, star birth. Astronomers captured these dramatic images as they explored the firework-like debris from the birth of a group of massive stars, demonstrating that star formation can be a violent and explosive process too.

1350 light years away, in the constellation of Orion (the Hunter), lies a dense and active star formation factory called the Orion Molecular Cloud 1 (OMC-1), part of the same complex as the famous Orion Nebula. Stars are born when a cloud of gas hundreds of times more massive than our Sun begins to collapse under its own gravity. In the densest regions, protostars ignite and begin to drift about randomly. Over time, some stars begin to fall toward a common center of gravity, which is usually dominated by a particularly large protostar — and if the stars have a close encounter before they can escape their stellar nursery, violent interactions can occur.

About 100 000 years ago, several protostars started to form deep within the OMC-1. Gravity began to pull them together with ever-increasing speed until 500 years ago two of them finally clashed. Astronomers are not sure whether they merely grazed each other or collided head-on, but either way, it triggered a powerful eruption that launched other nearby protostars and hundreds of colossal streamers of gas and dust out into interstellar space at over 150 km/s. This cataclysmic interaction released as much energy as our Sun emits in 10 million years.

Fast forward 500 years, and a team of astronomers led by John Bally (University of Colorado, USA) has used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to peer into the heart of this cloud. There they found the flung-out debris from the explosive birth of this clump of massive stars, looking like a cosmic version of fireworks with giant streamers rocketing off in all directions.

Such explosions are expected to be relatively short-lived, the remnants like those seen by ALMA lasting only centuries. But although they are fleeting, such protostellar explosions may be relatively common. By destroying their parent cloud, these events might also help to regulate the pace of star formation in such giant molecular clouds.

This video takes the viewer deep into the famous constellation of Orion (The Hunter). Hidden behind the glowing gas, dark dust and bright young stars of the Orion Nebula complex lies a strange object — the remains of a 500-year-old interaction of recently formed stars. A new image from ALMA, which reveals this feature more clearly than ever before, is shown at the end of the sequence. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), J. Bally/H. Drass et al./N. Risinger (skysurvey.org). Music: Johan B. Monell

Hints of the explosive nature of the debris in OMC-1 were first revealed by the Submillimeter Array in Hawaii in 2009. Bally and his team also observed this object in the near-infrared with the Gemini South telescope in Chile, revealing the remarkable structure of the streamers, which extend nearly a light-year from end to end.

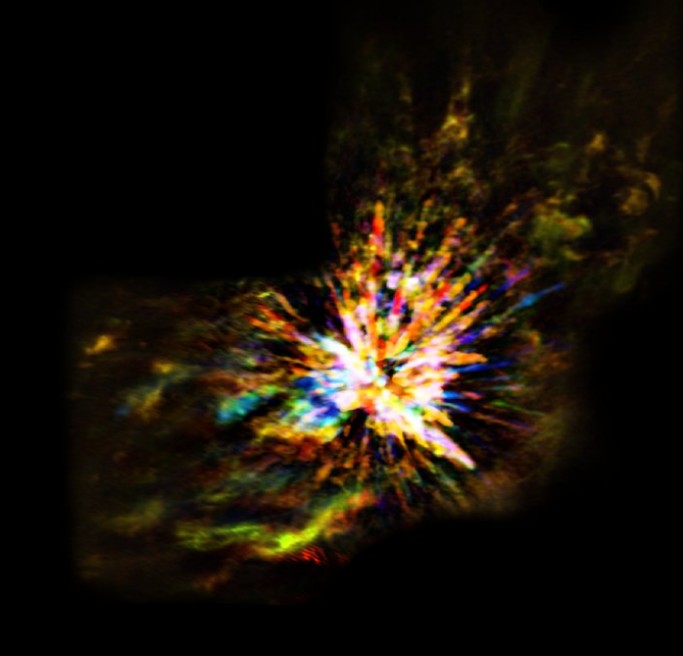

The new ALMA images, however, showcase the explosive nature in high resolution, unveiling important details about the distribution and high-velocity motion of the carbon monoxide (CO) gas inside the streamers. This will help astronomers understand the underlying force of the blast, and what impact such events could have on star formation across the galaxy.

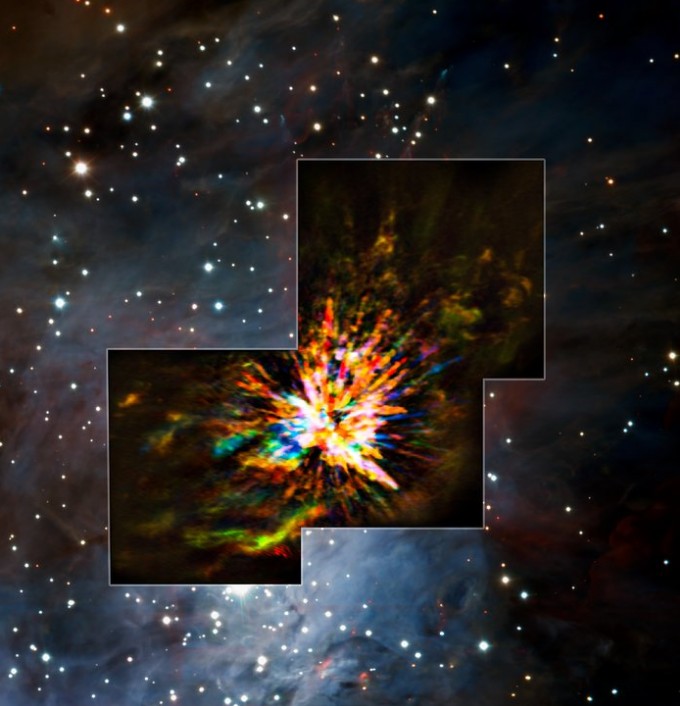

The colors in the ALMA data represent the relative Doppler shifting of the millimetre-wavelength light emitted by carbon monoxide gas. The blue color in the ALMA data represents gas approaching at the highest speeds; the red color is from gas moving toward us more slowly. The background image includes optical and near-infrared imaging from both the Gemini South and ESO Very Large Telescope. The famous Trapezium Cluster of hot young stars appears towards the bottom of this image. The ALMA data do not cover the full image shown here. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), J. Bally/H. Drass et al.

Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), J. Bally/H. Drass et al.

ALMA and VLT views of a stellar explosion in Orion. The background is an infrared image from the HAWK-I camera on ESO's Very Large Telescope. The ALMA data only cover the region marked by the box. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), J. Bally/H. Drass et al.

This video sequence compares a new ALMA image of an explosive event in the Orion star forming region with an image taken in infrared light using the HAWK-I camera on ESO's Very Large Telescope. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/J. Bally/H. Drass et al. Music: Johan B. Monell

ALMA is the most powerful telescope for observing the cool Universe — molecular gas and dust. ALMA studies the building blocks of stars, planetary systems, galaxies and life itself. By providing scientists with detailed images of stars and planets being born in gas clouds near our Solar System, and detecting distant galaxies forming at the edge of the observable Universe, which we see as they were roughly ten billion years ago, it lets astronomers address some of the deepest questions of our cosmic origins.

It was inaugurated in 2013, but early scientific observations with a partial array began in 2011.

Source: ESO

Reference:

"The ALMA view of the OMC1 explosion in Orion" – Bally et al. – Astrophysical Journal (2017) – Draft version

Featured image credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), J. Bally/H. Drass et al.

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules.