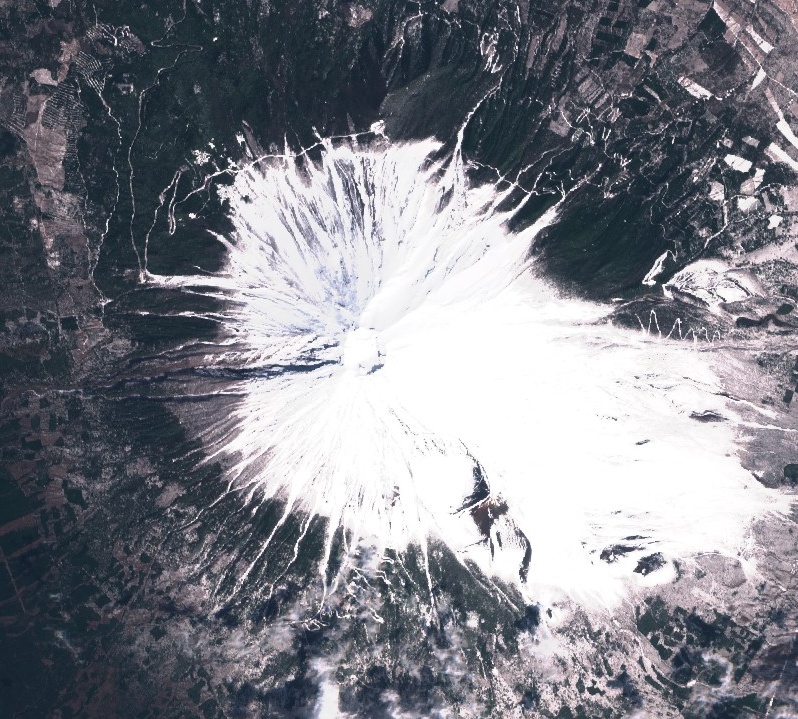

Simulation shows new eruption at Mount Fuji could paralyze Tokyo in just 3 hours, Japan

Japan’s capital Tokyo could end up paralyzed within just three hours if a major eruption of Mount Fuji– 100 km (62 miles) southwest of the city– were to happen today, as shown in a recent simulation by the government’s Central Disaster Management Council. In just a few hours, Tokyo could end up with major power, drinking water, and traffic disruptions. Fuji is one of Japan’s “Three Holy Mountains” along with Mount Tate and Mount Haku.

Mount Fuji’s last eruption– also called the Hoei eruption– took place in December 1707 (VEI 5). It spewed ash for more than two weeks, with a few centimeters accumulating in the city of Edo, present-day Tokyo.

The simulation showed what would have happened if the same scale eruption were to happen today, engulfing the greater Tokyo with thick volcanic ash. Based on similar eruptions that have happened in Japan and overseas, the researchers calculated the effects that different heights of ash would create.

The findings showed that the ash would possibly reach central Tokyo, as well as the neighboring prefectures of Kanagawa, Chiba, and Saitama– just three hours after the eruption.

However, since the areas would differ in terms of the wind direction, the council divided the findings into three scenarios:

– first, with a strong wind blowing from the west, similar to the Hoei eruption;

– second, with a strong west-southwest wind hitting Tokyo directly, causing a major impact;

– third, with comparatively huge changes in the wind, which could also affect Mount Fuji’s western portion.

For the first two cases, it was found that ash would accumulate in the metropolitan area after a few hours. All railway services would be disrupted, and even a very small amount of ash would trigger a system malfunction. Trains would stop running across the Kanto region and the prefectures of Yamanashi and Shizuoka.

In the event of rainfall, at least 3 mm (0.1 inches) of ash would cause an electrical shortage, leading to a widespread blackout in central Tokyo. Water supplies and subway systems would be halted.

In areas that would accumulate at least 300 mm (11.8 inches) of ash with rain, wooden homes would not be able to bear the weight and would eventually collapse.

With the latest forecasts, the Cabinet Office, together with relevant agencies and ministries, is set to begin considering related issues, including how to clear up the volcanic ash, and what would be the potential waste sites.

“A mistake in the early response could leave tens of millions of people stranded, and it may not be possible to distribute supplies,” said research leader Toshitsugu Fujii, professor emeritus of the University of Tokyo.

“It’s important to prepare a system to handle the situation in advance.”

The last known eruption of this volcano took place from December 16, 1707 to ~February 24, 1708. It was ranked as a VEI 5 (Volcanic Explosivity Index). The eruption started 49 days after M8.6 earthquake on October 28 — Japan’s largest earthquake before the 2011 Tohoku earthquake.

While there were no direct deaths associated with the eruption, many people died (some estimates suggest 20 000) as a consequence of massive amount of ash released by the volcano (~800 million m3). The agricultural sector was decimated, causing many people to starve to death. Ash also ended up in streams and rivers, filling them up and even damming them. In August, 1708, these dams broke, causing a flood of mud and volcanic ash, which blanketed the downstream regions.OSU

The volcano is located at the triple junction where the Amurian Plate, the Okhotsk Plate, and the Philippine Sea Plate meet. Those plates form the western part of Japan, the eastern part of Japan, and the Izu Peninsula respectively.

Geological summary

The conical form of Fujisan, Japan’s highest and most noted volcano, belies its complex origin.

The modern postglacial stratovolcano is constructed above a group of overlapping volcanoes, remnants of which form irregularities on Fuji’s profile. Growth of the Younger Fuji volcano began with a period of voluminous lava flows from 11 000 to 8 000 years before present (BP), accounting for four-fifths of the volume of the Younger Fuji volcano.

Minor explosive eruptions dominated activity from 8 000 to 4 500 BP, with another period of major lava flows occurring from 4 500 to 3 000 BP.

Subsequently, intermittent major explosive eruptions occurred, with subordinate lava flows and small pyroclastic flows.

Summit eruptions dominated from 3 000 to 2 000 BP, after which flank vents were active.

The extensive basaltic lava flows from the summit and some of the more than 100 flank cones and vents blocked drainages against the Tertiary Misaka Mountains on the north side of the volcano, forming the Fuji Five Lakes, popular resort destinations.

The last confirmed eruption of this dominantly basaltic volcano in 1707 was Fuji’s largest during historical time. It deposited ash on Edo (Tokyo) and formed a large new crater on the east flank.

This volcano is located within the Fujisan, sacred place and source of artistic inspiration, a UNESCO World Heritage property.

Featured image: Mount Fuji as seen from Chureito Pagoda. Credit: Giuseppe Milo

In the beginning of this year Hiroki Kamata, a professor of volcanology at Kyoto University said that Mount Fuji is on standby for the next eruption. Given the 1707 Hoei Eruption was likely triggered by a magnitude 8.6 earthquake that struck south-central Japan 49 days earlier, Kamata believes there is a high likelihood that a magnitude 9 Nankai Trough earthquake — should it happen in the near future as forecast by the government — would do the same. But Takayoshi Iwata, director of the Center for Integrated Research and Education of Natural Hazards at Shizuoka University, offered a more nuanced view. “It’s true that history has shown eruptions can be caused by earthquakes, but there were also times Mount Fuji erupted of its own accord, so it’s not necessarily the case there is a correlation with quakes,” he said.