Ground shaking, landslides, volcanic activity and tsunami associated with M5.7 earthquake at Lake Taupō, New Zealand

GeoNet experts have been busy collecting and analyzing data to help them understand exactly what happened during and following the M5.7 earthquake at Lake Taupō on November 30, 2022, including ground shaking, landslides, volcanic activity, and a tsunami.

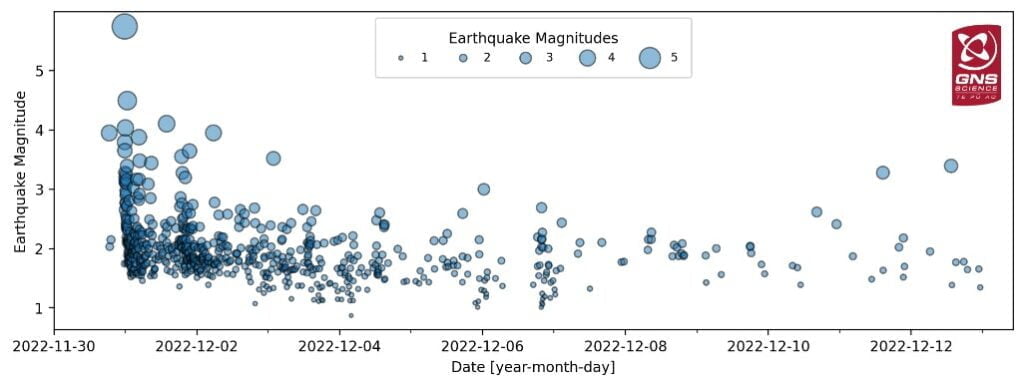

In their latest update released on December 14, GeoNet said the initially reported magnitude of 5.6 was increased to M5.7, reflecting the greater accuracy they have been able to bring to the earthquake analysis since it happened.

From November 30 to December 14, a total of 680 aftershocks were located, with the most recent felt aftershock being a M3.4 on December 12.

“The aftershock sequence (size of events and numbers) is as we would have expected for a mainshock of M5.7,” GeoNet’s experts said.

The magnitude and rate of aftershocks have started to decline but are expected to continue for several weeks.

In addition to the shaking of the ground during the earthquake, GNSS (GPS) instrument at Horomatangi reef (TGHO) moved 18 cm (7.08 inches) upwards during the earthquake and 25 cm (9.84 inches) to the southeast, which is the largest ever recorded ground movement at this location.

The station has also shown what is called ‘post-seismic deformation’ — it moved a further 4 cm (1.57 inches) to the southeast in the week following the earthquake. GNSS stations onshore are recording a much smaller movement (~10 to 20 mm / 0.39 to 0.78 inches) associated with the earthquake.

A small tsunami was generated in Lake Taupō on the night of the M5.7 earthquake. The waves traveled across the lake and surged a few meters across many beaches, leaving behind some strands of pumice, sticks and sand. The larger surge at Wharewaka Point, where the beach is known to have retreated by some 20 m (65 feet), may be associated with a possible underwater landslide. It is expected that models generated in the coming weeks will allow us to understand these details further.

“We have surveyed the deposits and found that the tsunami wave pushed debris almost 1 m (3.3 feet) above the lake level, when it reached the western shores at Kuratau and on the east side of the lake at Motutere.”

In some places, the lakeshore had been undercut by waves and small areas had collapsed a meter or so back.

The tsunami had less impact on the northern shores, for example at Whakaipo Bay where the wave left pumice debris less than 30 cm (1 feet) higher and less than 1 m (3.3 feet) inland from the high-water mark.

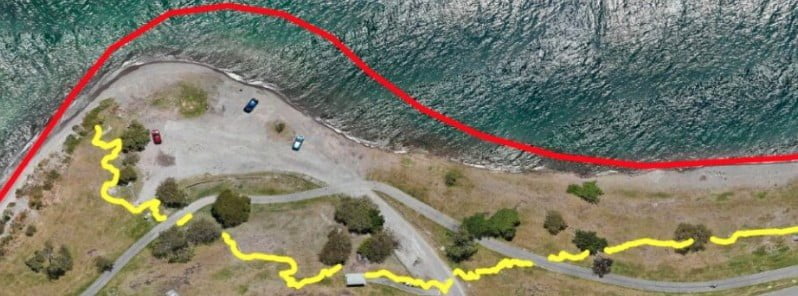

Little or no change was seen at Kinloch, Acacia Bay, or in the western bays. However, major changes happened at Wharewaka point near Taupō, with substantial washout of the foreshore and beach, and pumice debris stranded to a maximum of about 40 m (131 feet) inland from the lake.

“We are running computer models of the tsunami to understand how it might have been generated and spread across the lake. We are also investigating the specific cause of the effects at Wharewaka Point.”

More than 30 landslide events have been triggered by the M5.7 earthquake. This is not unexpected, given the severity of the shaking, and the timing of the earthquake, which followed several weeks of particularly wet weather.

Most of them were small slips on steep cut slopes close to roads (particularly in northern regions, close to Acacia Bay), while larger rockfalls (perhaps up to the size of a bus) were identified closer to the epicenter in the vicinity of Hatepe.

Most were generated on the White Cliffs along the eastern lake shore north of Hatepe, just 7 km (4.3 miles) from the earthquake epicenter.

Here, a several-hundred-meter-long (though relatively shallow) section of the cliffs collapsed into the lake, generating a large white plume of sediment that could still be seen stretching north along the coastline several days after the earthquake.

Aside from the rockfalls on the White Cliffs, the most notable single earthquake-triggered land movement, was located over 15 km (9.3 miles) north of the epicenter, at Wharewaka Point.

It is possible an underwater landslide occurred at the location of the popular swimming beach, causing 170 m (557 feet) of the shoreline to subside into the lake, with a maximum retreat of up to 20 m (65 feet). Whilst still under investigation it is possible that the collapse of the beach into the lake drew water in behind it, generating the local tsunami that washed up onto the picnic area behind it.

Underwater landslides are known to be some of the largest landslides on earth and can trigger tsunamis, however, there is currently no evidence to suggest the Wharewaka Point landslide generated the larger lake-wide tsunami observed following this earthquake.

Minor volcanic unrest has been ongoing at Taupō Volcano since May 2022, and the Volcanic Activity Level (VAL) was raised to 1 in September 2022.

This recent earthquake activity is within the range that had previously been anticipated and is consistent with minor volcanic unrest. This activity does not warrant a move to a higher volcanic alert level, GeoNet said.

Prior to November 30, the unrest had been characterized by hundreds of small, typically non-felt, earthquakes and a few larger events (M3.5 to M4.2) that had been felt. This seismic activity appears to be a mainshock-aftershocks sequence that has interrupted an otherwise steady unrest record to date. None of these earthquakes are volcanic types.

Taupō has had 18 episodes of unrest in the past 150 years, lasting for months to years. None of them led to an eruption. Based on this history, the current unrest period could continue for many weeks to months, at varying rates or intensities.

Geological summary

Taupo, the most active rhyolitic volcano of the Taupo volcanic zone, is a large, roughly 35 km (21 miles) wide caldera with poorly defined margins. It is a type example of an “inverse volcano” that slopes inward toward the most recent vent location.

The caldera, now filled by Lake Taupo, largely formed as a result of the voluminous eruption of the Oruanui Tephra about 22 600 years before the present (BP).

This was the largest known eruption at Taupo, producing about 1 170 km3 (281 mi3) of tephra. This eruption was preceded during the late Pleistocene by the eruption of a large number of rhyolitic lava domes north of Lake Taupo.

Large explosive eruptions have occurred frequently during the Holocene from many vents within Lake Taupo and near its margins.

The most recent major eruption took place about 1 800 years BP from at least three vents along a NE-SW-trending fissure centered on the Horomotangi Reefs. This extremely violent eruption was New Zealand’s largest during the Holocene and produced the thin but widespread phreatoplinian Taupo Ignimbrite, which covered 20 000 km2 (7 722 mi2) of North Island.2

Reference:

1 Taupō Earthquake Update – GeoNet – December 14, 2022

2 Taupo – Geological summary – GVP

Featured image credit: GeoNet

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules.