World’s longest recorded earthquake lasted for 32 years

The devastating M8.5 earthquake that shook Sumatra, Indonesia, in 1861 was long believed to be a sudden rupture on a previously quiescent fault. However, new research showed that tectonic plates below the island had been slowly crashing against each other for 32 years prior to the catastrophic event. The silent earthquake, known as a slow-slip event, was the longest sequence of its kind ever detected on Earth.

Slow-slip earthquakes occur when two segments of crust move against each other. Some faults are now being monitored for a slow slip with GPS technology or seismic instruments, but it was difficult back then to trace such events on remote faults or before the GPS became available.

Near the Simeulue island off the coast of Sumatra, coral growth patterns record the up and down movements along the fault of the 1861 earthquake, providing scientists a window to the history of the fault between 1738 to 1861.

Researchers from the Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore identified the event by studying coral along the fault line.

Coral cannot grow when exposed to the air, so layers of dead coral can also unveil sea levels. When the local sea-level changes as a result of tectonics, the changes become visible in corals' skeletal growth records, explained Rishav Mallick, a doctoral student at the NTU and the study's lead author, said wh

The corals reveal that Simeulue had been subsiding for 90 years steadily by up to 2 mm (0.07 inches) every year, which is consistent with the fault's background motion.

However, around 1829, it suddenly started sinking up to seven times faster, Mallick said. This suggests that the fault had started to move in a slow-slip earthquake. "It's a very sharp change," he added. The rapid subsidence continued until the devastating 1861 earthquake.

For a long time, "the assumption was that, between the big earthquakes, the system was simple”: two sections of crust get locked against each other at the fault, building up strain until—crack—they break free with an earthshaking shudder," Kevin Furlong, a geoscientist at Pennsylvania State University, who was not involved in the study.

If a slow-slip motion is missed, researchers may miscalculate where the strains are on a fault and how strong the fault can produce a quake. "Once we can better define the locked region, we can better define the magnitude of an earthquake that can occur."

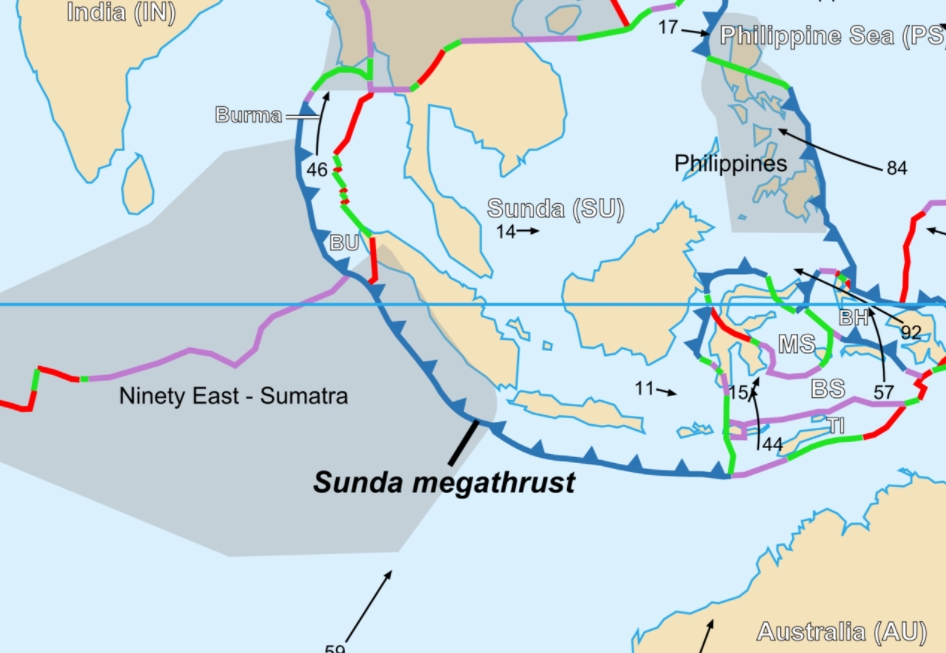

Image: Plate tectonic of Sunda Megathrust, Indonesia. Credit: WikiMedia

Reference

"Long-lived shallow slow-slip events on the Sunda megathrust" – Mallick, R., et al. – Nature Geoscience – https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00727-y

Abstract

During most of the time between large earthquakes at tectonic plate boundaries, surface displacement time series are generally observed to be linear. This linear trend is interpreted as a result of steady stress accumulation at frictionally locked asperities on the fault interface. However, due to the short geodetic record, it is still unknown whether all interseismic periods show similar rates, and whether frictionally locked asperities remain stationary. Here we show that two consecutive interseismic periods at Simeulue Island, Indonesia experienced significantly different displacement rates, which cannot be explained by a sudden reorganization of locked and unlocked regions. Rather, these observations necessitate the occurrence of a 32-year slow-slip event on a shallow, frictionally stable area of the megathrust. We develop a self-consistent numerical model of such events driven by pore-fluid migration during the earthquake cycle. The resulting slow-slip events appear as abrupt velocity changes in geodetic time series. Due to their long-lived nature, we may be missing or mis-modelling these transient phenomena in a number of settings globally; we highlight one such ongoing example at Enggano Island, Indonesia. We provide a method for detecting these slow-slip events that will enable a substantial revision to the earthquake and tsunami hazard and risk for populations living close to these faults.

Featured image credit: Pixabay

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules.