East Coast Tsunami risk study

The US East Coast tsunami posibility was main target of new sonar mapping study. Researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey, along with other governmental and academic partners, have been researching the potential for tsunamis generated by landslides in submarine canyons in the mid-Atlantic to strike the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coasts for about past five years.

The investigation was requested by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which is concerned about the potential impact tsunamis might have on new and existing nuclear power plants (considering the devastating tsunami in Japan in March that sparked the greatest nuclear disaster). According to study, the leading potential source of East Coast tsunami would be landslide along the submerged margin of the North American continent. Another scenario is waves kicked up by an asteroid splashing into the ocean.

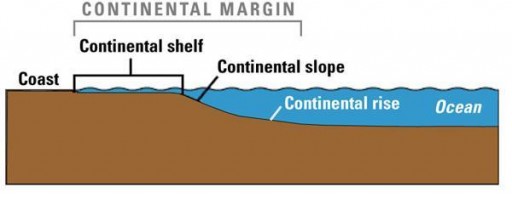

Key areas of the Atlantic continental margin were mapped in high resolution. Although this is one of the best-mapped continental margins in the world, significant gaps still remain along the upper slope and shelf where potentially dangerous submarine landslides might occur. Given the immense size of the regions investigated, it has taken many years of data collection and integration of existing data sets in order to produce seafloor maps with the resolution needed to identify all the features that researchers were interested in according to U.S. Geological Survey research marine geologist Jason Chaytor.

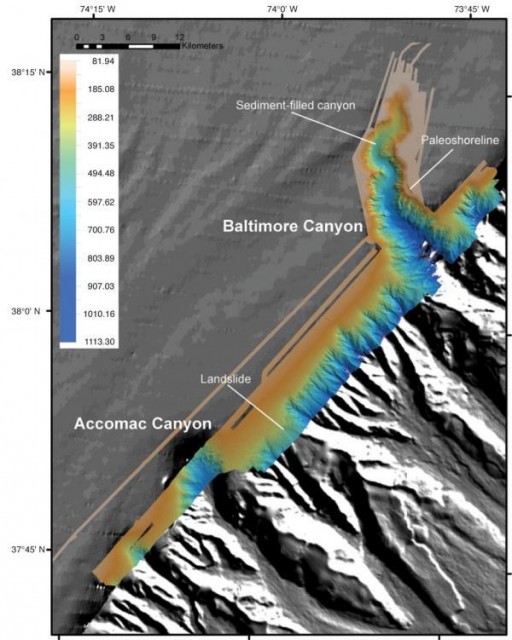

A sonar mapping cruise taken in June to the Baltimore, Washington and Norfolk Canyons and selected regions of the continental shelf between the canyons marked the first field effort of the multiyear Deep-Water Mid-Atlantic Canyons Project. Using echosounders installed on the hull of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ship Nancy Foster, the science team mapped canyons and shelf regions at high resolution over more than 1,000 square kilometers (380 square miles) of seafloor from south of Cape Hatteras to Baltimore Canyon, which runs from offshore North Carolina to the eastern tip of Long Island.

The science team’s preliminary analysis of these new data revealed the presence of steep, sharp, stepped escarpments, or slopes, rimming the upper parts of each of the mapped canyons. These may be submerged ancient shorelines cut during times of lower sea level, the most recent of which occurred during the last glacial period, which ended about 19,000 years ago. Although the researchers do not at this time feel there is any connection between these features and tsunami hazards, they may provide important insights into the development of the canyons and help us understand the role of changing sea level in the evolution of the Atlantic coast.

A number of submarine landslides, some previously unknown, were either partly or completely mapped. Having accurate information on the number of submarine landslides, in addition to their characteristics such as their size and the water depth they occur in, the style in which they fail, and the properties of the soil and rock involved in the landslide, are important in determining whether or not they might have generated a tsunami. This information is often used in numerical modeling of landslide-generated tsunami waves.

The scientists have recently begun the difficult task of collecting long core samples of sediment from the sites of large landslides, a critical step in determining when they happened and how often they and their associated tsunamis are likely to occur. The evaluation of submarine landslides as potential tsunami sources along the U.S. East Coast and the Gulf of Mexico and the investigation of submarine canyon systems in the Atlantic are ongoing projects. (OurAmazingPlanet)

The scientists detailed their findings in the September/October issue of the U.S. Geological Survey newsletter Sound Waves. They will present additional information at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting in San Francisco in December.

When soil, rock, and other earth debris can no longer hold it together and gives way to gravity, landslides happen. The downward force of a landslide can move slowly, (a mere millimeters per year) or quickly with disasterous effects. Landslides can even occur underwater, causing tidal waves and damage to coastal areas. These landslides are called submarine landslides. They can be triggered by earthquakes, volcanic activity, changes in groundwater, a disturbance or change of slope. Intense rainfall over a short period of time tends to trigger shallow, fast-moving mud and debris flows. Slow, steady rainfall over a long period of time may trigger deeper, slow-moving landslides. (LLM)

On November 9 the PACWAVE11 tsunami excercise was held. Two of ten scenarios showing tsunami waves reaching US East Coast – tsunamis generated near Kamchatka and Aleutian Islands (images above). See tsunami time travel maps here.

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules.