Three theories of planet formation busted

The more new planets we find, the less we seem to know about how planetary systems are born, according to a leading planet hunter. With the tally of confirmed planets orbiting other stars now more than 500, planet hunters are heading for a golden age of discovery, said Geoffrey Marcy of the University of California, Berkeley.

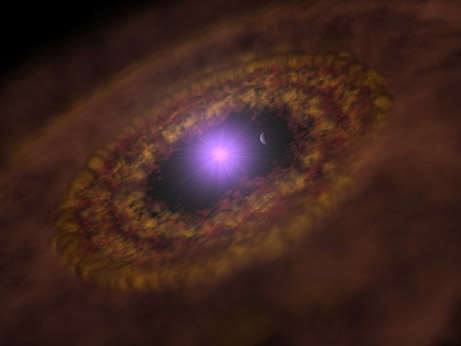

But that bonanza has been a headache for theoreticians, he said, because many of the newly discovered star systems defy existing models of how planets form. Current theory holds that planets are made from disks of gas and dust left over after star birth. In our solar system, it's long been thought that the large, gassy planets such as Jupiter and Saturn initially took shape in the far reaches and then migrated inward, as gravitational drag from leftover gas and dust eroded their orbits.

The migration process halted when most of the gas and dust had been swept up to make various objects, leaving the planets more or less where we find them today. In theory, other stars with planets should have gotten similar starts. But according to Marcy, the theory has implications not born out in reality.

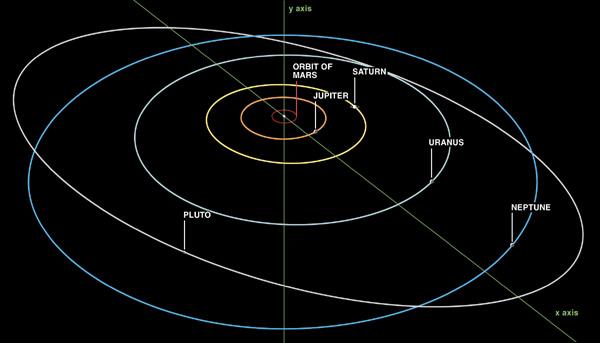

Implication #1: All planetary orbits should be roughly circular.

It's possible some planets are born with eccentric orbits, moving around their stars in elongated ovals. But as a migrating planet spirals closer toward its star, gravitational drag should smooth out its orbit, like an object circling a drain. The eight planets of our solar system all have roughly circular orbits, and models of planet-forming disks suggest most other star systems should be the same. In reality, though, only about one in three of the known exoplanets has a circular or near-circular orbit.

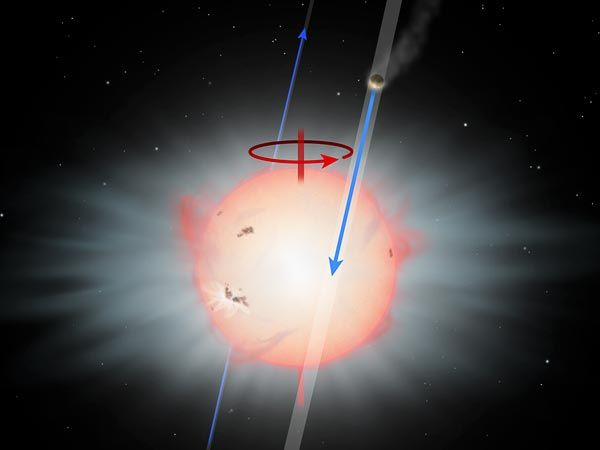

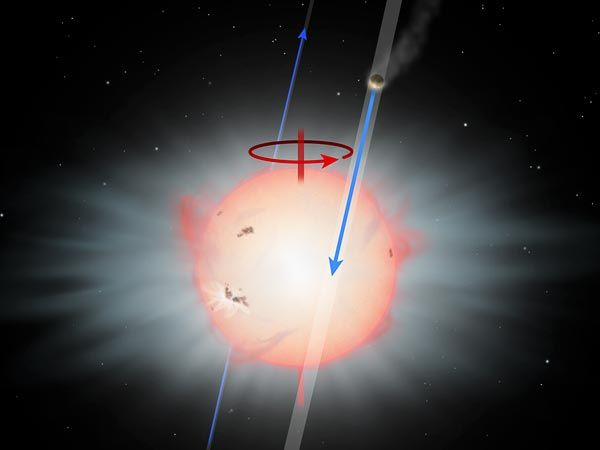

Implication #2: With minor exceptions, everything in a star system should orbit in the same plane and in the same direction.

The eight planets of our solar system orbit in the same direction along what's called the ecliptic, a flat plane that's nearly aligned with the sun's equator. This makes sense if planets take shape inside the flat disks of material that rotate around newborn stars. Models are based on the notion that gravitational drag in these disks is the main influence on planets as they migrate. Based on this theory, planets should stay in the ecliptic and continue to follow their stars' rotations. However, about one in three exoplanets' orbits are "misaligned." Some orbit in the opposite directions as their stars' rotations and others are tilted out of the ecliptic, like weather satellites crossing over Earth's Poles rather than the Equator. "Orbital inclinations are all over the map," Marcy said.

Implication #3: Neptune-size planets should be rare across the universe.

Theories of gas drag also say that planets between three times Earth's mass and Jupiter's mass should be relatively rare. That's because models suggest that migration speed is proportional to the mass of a planet, said astronomer Alessandro Morbidelli of the Laboratoire Cassiopee in Nice, France. Planets smaller than Earth can easily survive in the disk because they migrate slowly. Planets between an Earth mass to Uranus mass migrate so fast that they should be engulfed by the central star. Planets that grow fast enough to become gas giants eat up all the gas around them, slowing their migration speeds and giving them a chance to survive.

Based on what planet-hunters are finding, though, UC Berkeley's Marcy argues that there are too many Neptune-size worlds for the theory to be right. (See "Six New Planets: Mini-Neptunes Found Around Sunlike Star.")

The size range where there should be the fewest planets—3 to 15 times the size of Earth—are actually the most common. Planets substantially smaller than this are still too hard to detect for accurate statistics.

Marcy thinks part of the problem is that theoreticians have paid too much attention to interactions with gas and dust and not enough attention to interactions between planets.The problem, he said, is that the theory is so math-intensive that a single detailed simulation can take months of computer time. "You can only do a small number of simulations" in the time allotted, Levison said.

To run enough simulations to get a meaningful distribution of possible results, he said, it's necessary to use stripped-down versions of these models. But the "quicker" models come at a price, and their failure to match exoplanet reality doesn't necessarily mean the theory is wrong.

- Three Theories of Planet Formation Busted, Expert Says

- New Planet Found; Star's Fourth World Stumps Astronomers

- Eccentric Exoplanet Gets Hot Flashes

- New Planets Found; Have Backward Orbits

- Five New Planets Found; Hotter Than Molten Lava

- Newborn Planet Found Orbiting Young Star

- Six New Planets: Mini-Neptunes Found Around Sunlike Star

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules.