Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 – Rare and unusually strong storm formed over Arctic

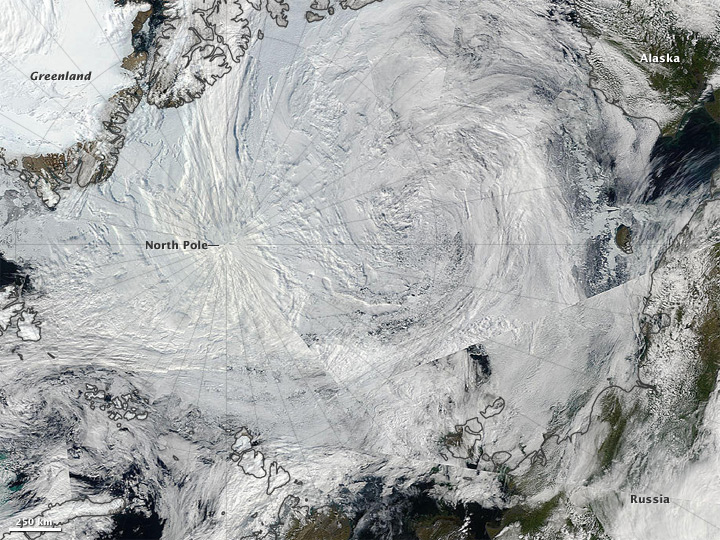

An unusually strong storm formed off the coast of Alaska on Aug. 5, then moved over the central Arctic. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite took the images that make up the mosaic during various passes over the North Pole on Aug. 6, when the storm was swirling over the middle of the Arctic Ocean. According to a NASA statement, there have only been about eight storms of similar strength during the month of August in the last 34 years of satellite records. And, it is very rare to see such strong storms in the Arctic during August. Polar lows are more usual in the winter.

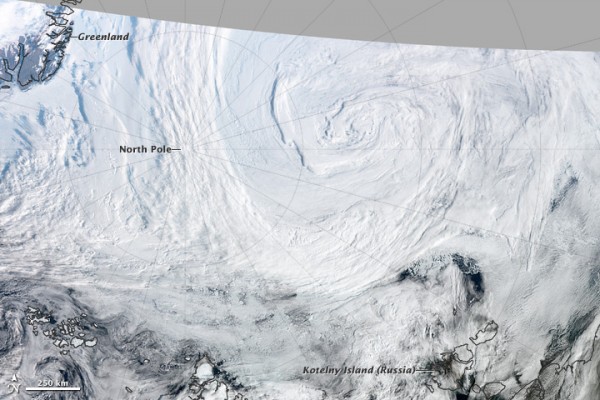

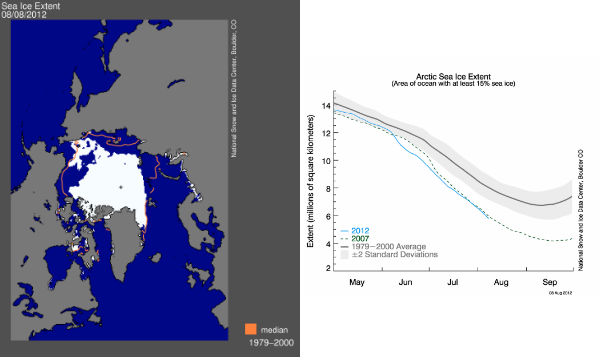

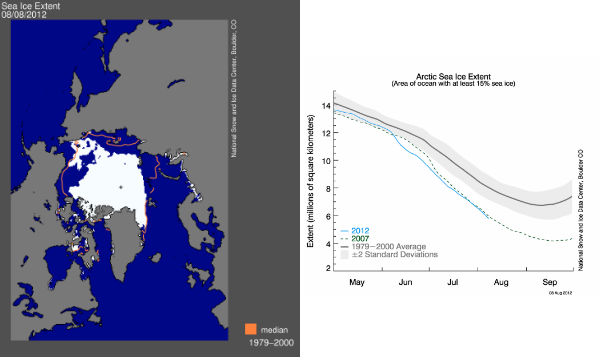

Storms like this can impact Arctic sea ice and cause it to melt rapidly as it churns the ice and potentially pushes it into warmer spots of water. According to Clarke Parkinson, a climate scientist with NASA Goddard, it seems that this storm has detached a large chunk of ice from the main sea ice pack. That large patch of sea ice in the East Siberian Sea is almost entirely detached from the main ice pack. The fact that the ice pack can get divided like this, is yet another sign that the ice is exceptionally thin, as thin ice gets pushed around more easily and melts quicker, leaving open space between thicker, slower moving ice floes. The sea ice extent chart from the Danish Meteorological Institute is showing huge drops and has almost reached a new record low.

This cyclone’s central sea level pressure reached about 964 millibars on August 6, 2012—a number more typical of a winter cyclone. That pressure puts it within the lowest 3 percent of all minimum daily sea level pressures recorded north of 70 degrees latitude.

This event could lead to a more serious decay of the summertime ice cover than would have been the case otherwise, even perhaps leading to a new Arctic sea ice minimum. The sea ice undergoes a seasonal cycle, spreading across the Arctic waters during winter and retreating in the warmth of summer. Usually, the ice reaches its minimum extent between the first week of September and around the end of the third week of the month, according to Walt Meier, a research scientist at National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

Strong summer cyclone churns over the Arctic

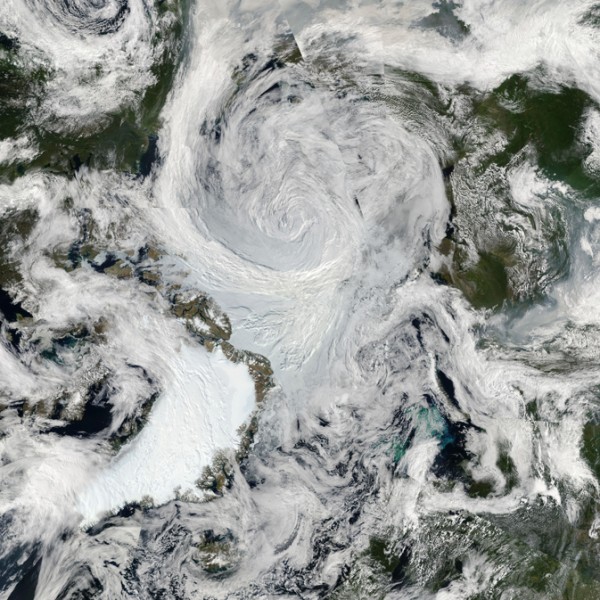

The Arctic summer storm – which perhaps will be known as the Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012, is slowly falling apart, losing its strength and position.

Two smaller systems merged on August 5 to form the storm, which at the time occupied much of the Beaufort-Chukchi Sea and Canadian Basin. On average, Arctic cyclones last about 40 hours; as of August 9, 2012, this storm had lasted more than five days. An unusually strong area of low pressure moved northward into the Arctic Ocean and intensified during the 05 August – 08 August 2012 time period — a storm this deep (965 hPa central pressure) is exceptional for the Arctic Ocean region, especially during the summer month of August.

The storm was moving poleward during the 05 August – 08 August time period. Barrow, Alaska was in the warm sector of the storm on 05 August, and recorded a daily high temperature of 15,5ºC or 60º F (with a peak wind gust from the southwest at 66 km/h or 41 mph). Two days later, strong cold air advection in the wake of the storm (with a peak westerly wind gust of 53 km/h or 33 mph) kept the daily high temperature at Barrow down to 3,8ºC or 39º F according to CIMSS satellite blog.

This storm formed and intensified near the Beaufort Sea and moved to the central Arctic Ocean where it will slowly lose its intensity over the next several days. Ordinarily, the Beaufort Sea and the Arctic Ocean are dominated by high pressure, so having a low pressure system form and intensify here is quite uncommon. Although, it has been happening with more frequency over the past few decades as pressures have dropped significantly in the Arctic during this time and are projected to drop even more during the next century by the global climate models.

Have a quick look at this short time-lapse video (bellow) of sea ice and weather conditions in the central Arctic Ocean from early July through August 8, recorded by one of the two autonomous cameras set on the sea ice near the North Pole each spring by a research team from the University of Washington.

Increasing number of Arctic cyclones

The number of cyclones affecting the Arctic appears to be increasing. According to a study of long-term Arctic cyclone trends authored by a team led by John Walsh and Xiangdong Zhang of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the number and intensity of Arctic cyclones has increased during the second half of the twentieth century, particularly during the summer. One study concluded that the total number of extratropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere would decline as the climate changed, but that the Arctic Ocean and adjacent areas would see slightly more and stronger summer storms.

Arctic cyclones spin counterclockwise in the northern regions and clockwise in the Antarctic, responding to the Coriolis effect like any other weather system. They can be up to 1,200 miles wide — large enough to fill a good portion of the North American continent, were they ever to drift that far south — but their influence on the temperate world’s weather, however well-documented, is largely indirect.These cyclones play an important part in the grand weather patterns of the Earth, and are coming under increased scientific scrutiny for this reason.

The birthplace of these cyclones is based on the combination of temperature, water currents, air flow over nearby land masses, another other processes which influence their creation. The best conditions for cyclone genesis is when an extremely cold low pressure area passes over warmer waters, sucking up moisture from the surface and turning it into clouds and snow. A cyclone can form in the polar regions in less than 24 hours, which contrasts with the cyclones of warmer latitudes, which require much longer to from. They move rapidly over the polar land and sea, bringing bitterly cold temperatures, massive amounts of snow which can produce white-outs that last for days, and extremely high winds.

Although they usually don’t venture below the boundaries of the polar regions at 68 degrees north or south, Arctic cyclones are powerful storms that affect the weather conditions of the rest of the world through various indirect means. They alter ocean salinity and ocean levels, can cause or prevent coastal flooding far away depending on their frequency and strength, and many other subtle effects. Since Arctic cyclones are low pressure areas, they tend to ‘suck’ air inwards towards them. Being such enormous lows, this indrawing of air has an immense reach. Strong cyclones in the winter will pull tropical air northwards, moderating temperatures, while flabby cyclones allow arctic air to move south, and result in bitterly icy cold spells.

Arctic cyclones and their effect on sea ice

Decades ago, a storm of the same magnitude would have been less likely to have as large an impact on the sea ice, because at that time the ice cover was thicker and more expansive. Sea ice this year in the Arctic has been trending below the 1979-2000 average, also potentially setting up a record low year. The influx of water from the Atlantic Ocean that feeds into the Arctic Ocean is warmer now than at any time in the 2,000 years prior. Recent years rank as the lowest on record since continuous record-keeping began in 1979, and scientists blame a combination of natural weather fluctuations, such as wind patterns, and global warming caused by the greenhouse gases humans emit. The problem is that while white ice reflects much of the sun’s energy back out into space, darker water absorbs more energy and holds on to it even after the sun’s presence over the far north is declining.

Arctic sea ice extent declined quickly in July, continuing the pattern seen in June. On August 1, ice extent was just below levels recorded for the same date in 2007, the year that saw the record minimum ice extent in September. Low sea ice concentrations are present over large parts of the western Arctic Ocean. Warm conditions dominated the weather for most of the Arctic Ocean and surrounding lands. For a brief period in early July, nearly all of the Greenland ice sheet experienced surface melt, a rare event.

The ice extent recorded for August 1 of 6.53 million square kilometers (2.52 million square kilometers) is the lowest in the satellite record. The previous record for the same date was set in 2007 at 6.64 million square kilometers (2.56 million square miles), when the current record low September ice extent was set.

This summer, the ocean has not been the only place where unusual melt has been observed in the Arctic. NASA researchers reported that for several days in early July, nearly the entire Greenland ice sheet experienced a brief period of surface melt, including at the summit of the ice sheet. Typically, about half of the ice sheet sees some surface melting during summer, but this tends to be confined to the lower elevations. The 2012 event was associated with a high-pressure weather pattern bringing unusually warm temperatures over the higher elevations of the ice sheet. While the event has not been seen previously in the 34-year satellite record, there is evidence in ice core data from Summit, Greenland of similar events occurring several times over the past few thousand years.

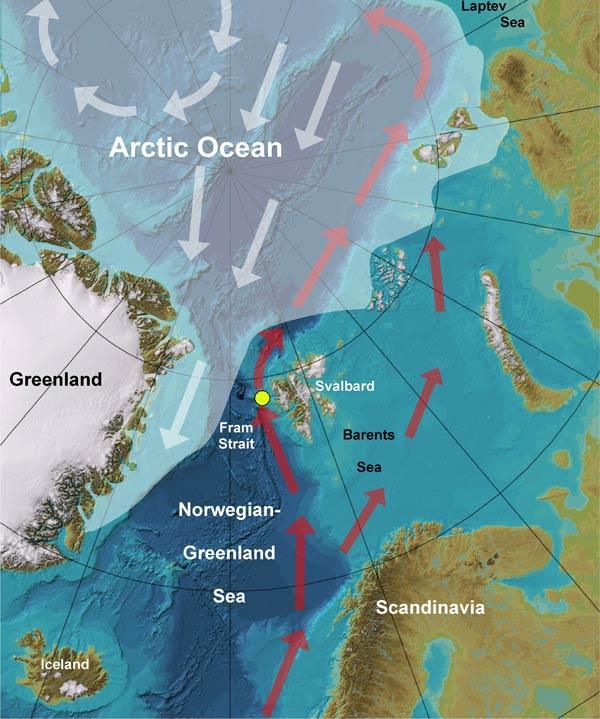

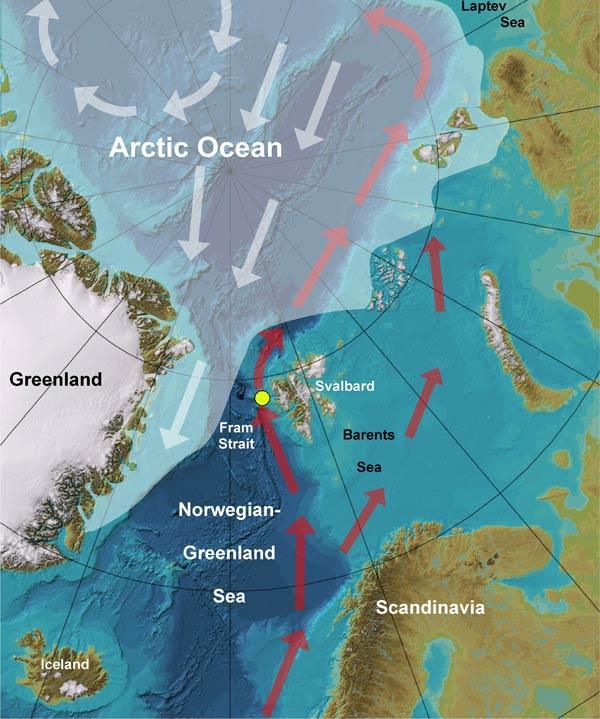

In the Arctic, the sea ice is typically about 2 to 3 meters (6.5 to 10 feet) thick. Then there is a layer of very cold water with a lower salt content that extends about 150 to 200 meters (500 to 650 feet) below the surface. Below that layer is warmer, higher-salt content water, that flows from the Atlantic through the Fram Strait. As the warmer water from the Fram Strait enters into the Arctic, the heat is transferred upward, melting the ice from below. Even more alarming, once the water from the Fram Strait enters the Arctic, it travels along the relatively shallow Canadian and Alaskan continental margins, where the shelves that lead up to the landmasses meet the deep sea. These areas are where the sea ice is formed, so the warmer water circulating through the area could change or even halt sea ice formation.

A significant loss of sea ice can also aggravate global warming through what is known as the albedo effect. White ice reflects much of the sun’s energy back out into space, while dark water absorbs it, bringing more heat into the natural system.

Sources: CIMSS, MODIS, POES, Suomi NPP, VIIRS, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), IceBridge Data Portal, XWeather, DotEarth, Environment Canada, ECMWF

[…] The Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 hit on Aug 5 and passed over the North Pole on Aug 6. […]

[…] The Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 has perhaps provided her with a little more clarity. Beyond that, the Chief Scientist’s statement was embarrassing: after all, even those most convinced that there is little danger of large immediate methane releases do not doubt the well established and drastic warming of the sea bottom precisely in the most methane-rich areas (see this paper), and Lena river discharge also greatly impacts the seabed in some of this same region, providing yet another mechanism for seabed warming. Slingo said, “At the moment, our estimates are that the increases in sea floor temperatures that have been observed have at the most been about one-tenth of a degree, except in one or two regions, like the West Spitsbergen Current.” […]

A very well written and a refreshingly neutral piece.

All the media resources tell the world the Arctic melting has been unprecedented this year. No mention of the facts.

The “Anthropogenic Global Warmistas” are all in a hoot, using big words copied off each other and just like the media, avoiding the reasons.

Post-glacial rebound! With the volcano activity picking up, it seems that pressure is being released off of the poles (melting-ice weight), squeezing the magma to the surface as the earth expands at the poles and gets stretched at the equator. And, as the ocean currents are in the process of stopping – or reversing – this appears to be a warm up (pun intended) to the super storms in the movie “The Day After Tomorrow?” Of course everyone should know from the ice core research, this cycle of earth-warming/ice age occurs approximately every 125,000 years (wiki: “ice age”). Enjoy the ride!

~ Thank You for sharing a hypothesis of what nature can only explain in actions..!!