Using infrasonic signals to detect and track tornadoes

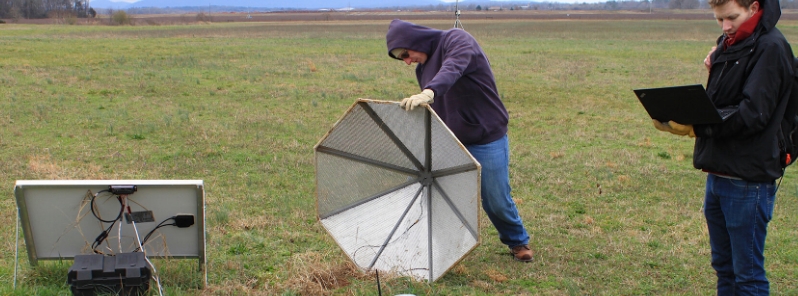

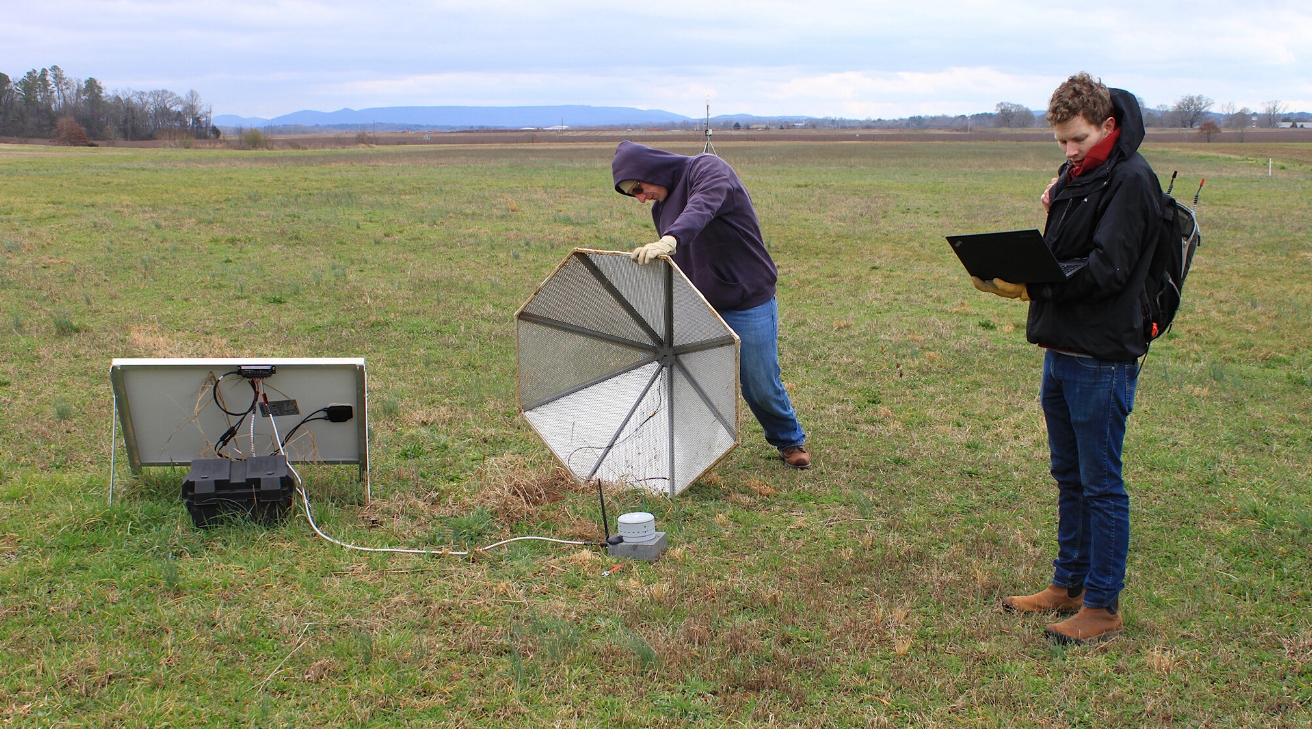

Researchers from the University of Mississippi are using an array of 12 infrasound sensors positioned across a pasture north of Huntsville in an effort to improve tornado warning methods.

Each sensor includes a 12-volt marine battery, cabling, domed windscreen, solar panel, and a device UM designed to record infrasound or acoustic signals at frequencies below what humans can hear. Tornadoes produce these low-frequency sounds, but the exact mechanism is still not understood.

"Radar does not detect tornadoes," said NCPA principal scientist Roger Waxler, also a UM research associate professor of physics and astronomy.

"The wavelengths are too long, and they are upward-looking. Tornadoes are currently detected by sight. The weather services use spotters (people). The radar shows the large scale rotation in storms that can spawn tornadoes but don't always do so."

"These particular arrays are being deployed specifically for research into tornado detection and tracking. The geometry of the arrays is tuned to the signals emitted by tornadoes," he further explained.

Detecting and tracking tornadoes are almost impossible, despite the evolving meteorological technology. However, the storms leave a definite mark and lasting damage as tornadoes rip through.

"The tornado infrasound research happening at NCPA has the potential for a significant impact in our region and across the nation," said Josh Gladden, UM vice chancellor for research and sponsored programs.

"Most importantly, it has the potential to augment and improve early warning systems in our communities, which could save lives."

"A further significant impact, however, is the potential to obtain much more tracking data for tornados than scientists currently have. This should lead to an improved understanding of what conditions specifically trigger tornados and what paths they follow," he added.

Image credit: Shea Stewart/UM

The NCPA infrasound group led by Waxler began examining the use of infrasound 20 years ago as a means of detecting secret nuclear weapon tests. Since then, the work has expanded, including monitoring hurricane intensity along the Atlantic seaboard, forensics of explosive events, studying winds in the upper atmosphere, and the tornado research.

"Over the past two to three years, we have been able to consistently demonstrate the ability to detect and accurately track tornadoes that have occurred in northern Alabama with sensor arrays that are as far away as 100 km (66 miles)," said Garth Frazier, a senior research scientist at NCPA and UM research associate professor of electrical engineering.

"We are still trying to gather sufficient data to increase understanding of what causes the sound to be generated and how to ensure that what we are hearing is caused by a tornado and not just a phenomenon related to thunderstorms. However, we are confident that the sound we have been detecting and tracking is not thunder."

The 12 sensors, planted next to a droning, are one array of seven that have been deployed this season in a line from northern Louisiana to northern Alabama. Choosing an exact array location is tricky as undesirable areas may affect the sensors. Fairly open areas provide solar power, but critters may also affect the equipment.

"From year to year, we may use the same sites if the landowner is willing and there are no issues with a particular site," said Hank Buchanan, an NCPA research and development engineer.

"The general idea is to position the arrays in a way that maximizes our chances of at least one array being in close enough proximity to capture acoustic data from a tornado if one should occur somewhere in the region."

"It's also beneficial to have more than one array get data on the same event. That standard, along with the general tendency for storms to move in a west-to-east direction in our region, left us with a line stretching from west to east across northern Alabama as our preferred area to deploy the arrays."

Data from the arrays is gathered every six to eight weeks. In February, Buchanan was accompanied by a fellow NCPA RND engineer, Brian Carpenter to download data from two recent tornadic events in the Tennessee River Valley and check the sensors.

Image credit: Shea Stewart/UM

About 100 km (60 miles) back toward Mississippi, the pair checked another array between Hillsboro and Moulton. The two found that these arrays are problematic during summer because they are commonly overgrown with kudzu, but winter has turned it brown and stopped its growth.

"What was once an area with abundant sunshine can be completely covered in shade in a matter of a few days that time of year," said Carpenter. "The batteries we use will last about 10 days at most with no sunlight reaching the solar panels."

"When functioning properly and receiving an ideal six hours of good sunlight a day, the power system will run indefinitely if unperturbed."

Downloading data from the sensors need an internet connection, even in the middle of nowhere. The sensors are designed to record infrasonic signals accurately. "Once the data is transferred to a computer, it can be processed using custom algorithms that detect when and where the tornadoes are located," said Frazier. "In the future, should the technology prove viable, this process can be fully automated to provide real-time information."

The tornado detection and tracking work have led to studies in various publications, but the researchers said more investigating needs to be done. "We have demonstrated that detecting and tracking of tornadoes using their infrasound emissions is feasible," Waxler stated.

"We are currently investigating the physical mechanism through which the infrasound is emitted from a tornado, and we are analyzing data from non-tornadic storms to see if there are any infrasound signals that might produce false positives." Waxler added, "I believe that with continued funding, this research would result in operational warning systems within about five years."

The sensors set out by researchers in fields in Louisiana and Alabama silently gather data that could save lives in the future, the researchers said.

Featured image credit: Shea Stewart/UM

Commenting rules and guidelines

We value the thoughts and opinions of our readers and welcome healthy discussions on our website. In order to maintain a respectful and positive community, we ask that all commenters follow these rules.