Unique cosmic coincidence – comets Encke and ISON to fly by Mercury

Comet Encke will fly by Mercury within 0.025 AU (3.74 million km) on November 18, 2013 and only a day later, Comet ISON will pass it at 0.24 AU. This is a unique cosmic coincidence and NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft, which is orbiting the planet, will take this golden opportunity for a point-blank investigation of both comets.

This double flyby is exciting, says Ron Vervack a member of the science team for MESSENGER spacecraft, but "it makes things a little crazy. We have to rush to complete our observations of Comet Encke, then do it all over again for Comet ISON. Everything is happening at more or less the same time."

MESSENGER was designed to study Mercury, not comets, “but it is a capable spacecraft with a versatile instrument package,” he adds. “We hope to get some great data.”

Onboard spectrometers will analyze the chemical makeup of the two comets while MESSENGER's cameras snap pictures of atmospheres, jets and tails.

In total, Vervack expects MESSENGER to gather 15 hours’ worth of data on Comet Encke and another 25 hours on Comet ISON. With that kind of observing time, discoveries are a distinct possibility.

Vervack says the first images will be beamed back and released to the public within days of the flybys.

Comet Encke is less known than ISON but it is our regular visitor and is coming back inside the orbit of Mercury every 3.3 years. It is also the source of Taurid meteor shower in early- to mid-November.

ISON is believed to be our first time visitor, and it will be interesting to observe the changes that will take part as it approaches the Sun.

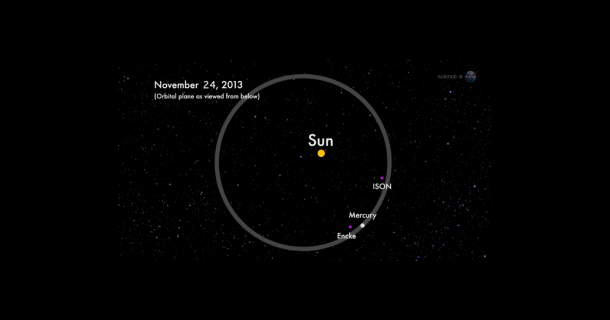

Update: November 24, 2013.

From MESSENGER's website:

On November 18, NASA's Mercury-orbiting MESSENGER spacecraft pointed its Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) at 2P/Encke and captured this image of the comet as it sped within 2.3 million miles (3.7 million kilometers) of Mercury's surface. The next day, the probe captured this companion image of C/2012 S1 (ISON), as it cruised by Mercury at a distance of 22.5 million miles (36.2 million kilometers) on its way to its late-November closest approach to the Sun.

MESSENGER's cameras have been acquiring targeted observations of Encke since October 28 and ISON since October 26, although the first faint detections didn't come until early November. During the closest approach of each comet to Mercury, the Mercury Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer (MASCS) and X-Ray Spectrometer (XRS) instruments also targeted the comets. Observations of ISON conclude on November 26, when the comet passes too close to the Sun, but MESSENGER will continue to monitor Encke with both the imagers and spectrometers through early December.

Comet Encke as seen from MESSENGER on November 17, 2013. Image credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington/Southwest Research Institute

The spacecraft has a view of the comets very different from that of Earth-based observers. "MESSENGER imaged Encke only a few days before its perihelion when it was at its brightest," explains Ron Vervack, of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, who is leading MESSENGER's comet-observation campaign. "That we are so close to the comet at this time offers a chance to make important observations that could shed light on its asymmetric behavior about perihelion."

In contrast, ISON did not pass as close to Mercury, but the comet was between the Earth and Mercury when it passed closest to MESSENGER. "We saw the side opposite to that visible from Earth," says Vervack, "so our images and spectra are complementary to observations from Earth made at the same time and could aid in understanding the variable activity of the comet as it approached the Sun."

On the day that Encke was closest to Mercury, the MDIS wide-angle camera scanned the comet with all of its 12 filters while the instrument's narrow-angle camera (NAC) snapped images of the rotating comet every 10 minutes to capture a full 360-degree view. The imaging campaign for ISON was similar, with the NAC capturing a series of stills every 30 minutes.

Several ground- and space-based NASA observatories, as well as many other observatories around the world, are collecting data on the comets. However, none will be able to collect simultaneous images and spectra from X-ray through near-infrared wavelengths when the comets are so close to the Sun, as will MESSENGER. Vervack expects MESSENGER to gather 15 hours worth of data on Encke and another 25 hours on ISON. "These observations of Encke and ISON fill a gap in heliocentric coverage to which most other observatories don’t have access," Vervack says.

Comet ISON as seen from MESSENGER on November 20, 2013. Image credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington/Southwest Research Institute

Scientists are still combing through the data collected by MASCS, but there are already confirmed detections of several molecules and atoms, including OH, NH, CS, oxygen, carbon, sulfur, and hydrogen. "Far-ultraviolet observations can't be made from ground-based observatories, and only a few instruments in space have been able to look at the comets in the ultraviolet," says Vervack. "The MASCS observations are therefore of great interest."

Scientists were also hoping to obtain the first definitive detections of cometary X-ray emission from silicon, magnesium, and aluminum. "NASA's Chandra X-ray space telescope has observed ISON and Encke and seen X-ray emission from them both," Vervack says. "We are able to make these observations when both comets are closer to the Sun, so the X-ray emissions have the potential to be much more intense." However, a series of large solar flares during the observations increased the contaminating background in the X-ray spectra and have complicated the analysis. "We can't help what the Sun does," says Vervack, "but we're going to analyze the data carefully to see if there are any detections to be had."

Taken together, the MESSENGER observations offer a varied science investigation of the comets. "Whereas the MDIS images will provide a global picture of the comet coma morphology, MASCS observations will inform us about the composition of the cometary ices and XRS may be able to tell us what the dust is made of," Vervack says.

"Comet encounters were not considered when the MESSENGER mission was designed," adds MESSENGER Principal Investigator Sean Solomon of Columbia University. "If Encke and ISON share a few of their secrets on the formation and evolution of the Solar System, the MESSENGER team will be delighted with the scientific bonus." Source: MESSENGER

Featured image: NASA

nasa will find a lie to avoid showing the picture of ''mercury going comet'', messenger will have great data but it will stay there!

I agree. Not many pics of Ison either. It is hard to believe the extent of Nasa lies but not seeing is believing. Something big must be going on or else lying by omission is suppose to drum up fear and public panic. Its one or the other.