Three strong earthquakes struck near the March 11, 2011, M 9.0 area within three hours

On May 19, 2012 JST three strong earthquakes struck near the March 11, 2011 magnitude 9.0 Great Tohoku earthquake and they all happened within three hours. For easier understanding of times when they occurred all earthquakes will be described in UTC time.

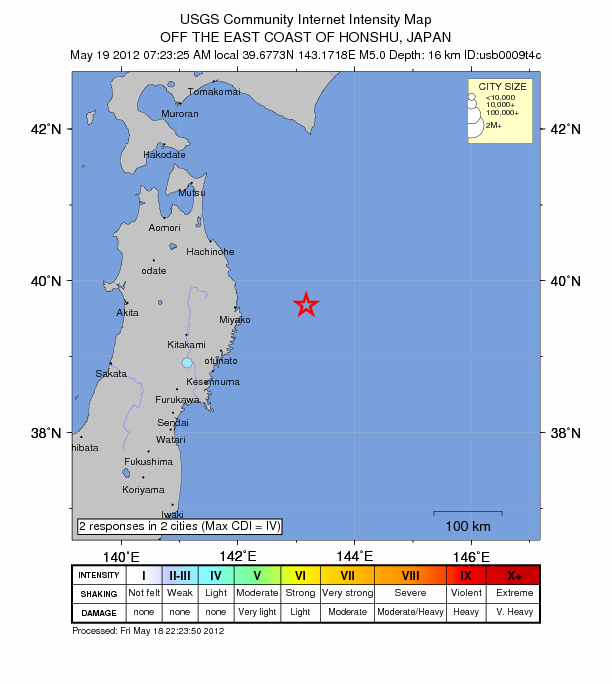

According to USGS, the first one occurred at 21:23 UTC on May 18, 2012 off the East coast of Honshu (39.677°N, 143.172°E) with magnitude 5.0 and recorded depth of 16.5 km (10.3 miles).

The second one was recorded 10 minutes later at 21:32 UTC on May 18 with magnitude 4.7 and recorded depth of 27.4 km (17.0 miles). The third one, two and a half hours later, at 00:08 UTC on May 19, with recorded depth of 22.1 km (13.7 miles) and magnitude 4.8.

JMA had the same values and recorded:

09:14 JST, 19 May 2012, 09:09 JST – Sanriku Oki M4.8

06:37 JST, 19 May 2012, 06:32 JST – Sanriku Oki M4.7

06:28 JST, 19 May 201,2 06:23 JST – Sanriku Oki M5.1

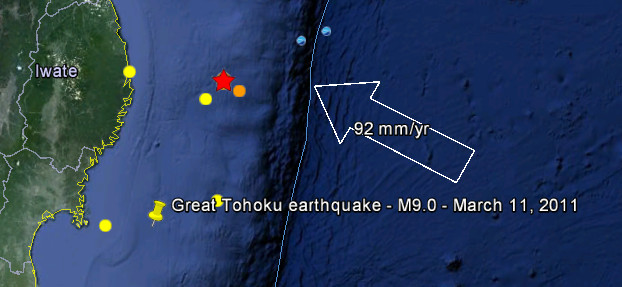

The distance from Great Tohoku M9.0 earthquake from March 11 last year was 162 km (101 miles):

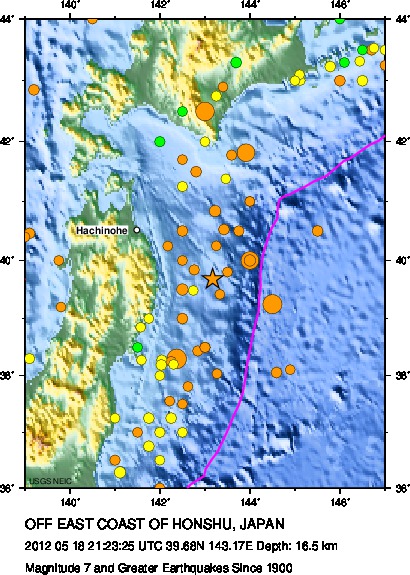

Historical seismicity of the area since 1900, magnitude 7+

The magnitude 9.0 Tohoku earthquake on March 11, 2011, which occurred near the northeast coast of Honshu, Japan, resulted from thrust faulting on or near the subduction zone plate boundary between the Pacific and North America plates. At the latitude of this earthquake, the Pacific plate moves approximately westwards with respect to the North America plate at a rate of 83 mm/yr, and begins its westward descent beneath Japan at the Japan Trench. Note that some authors divide this region into several microplates that together define the relative motions between the larger Pacific, North America and Eurasia plates; these include the Okhotsk and Amur microplates that are respectively part of North America and Eurasia.

The March 11 earthquake was preceded by a series of large foreshocks over the previous two days, beginning on March 9th with a M 7.2 event approximately 40 km from the epicenter of the March 11 earthquake, and continuing with another three earthquakes greater than M 6 on the same day.

The Japan Trench subduction zone has hosted nine events of magnitude 7 or greater since 1973. The largest of these, a M 7.8 earthquake approximately 260 km to the north of the March 11 epicenter, caused 3 fatalities and almost 700 injuries in December 1994. In June of 1978, a M 7.7 earthquake 35 km to the southwest of the March 11 epicenter caused 22 fatalities and over 400 injuries. Large offshore earthquakes have occurred in the same subduction zone in 1611, 1896 and 1933 that each produced devastating tsunami waves on the Sanriku coast of Pacific NE Japan. That coastline is particularly vulnerable to tsunami waves because it has many deep coastal embayments that amplify tsunami waves and cause great wave inundations. The M 7.6 subduction earthquake of 1896 created tsunami waves as high 38 m and a reported death toll of 22,000. The M 8.6 earthquake of March 2, 1933 produced tsunami waves as high as 29 m on the Sanriku coast and caused more than 3000 fatalities.

The March 11, 2011 earthquake was an infrequent catastrophe. It far surpassed other earthquakes in the southern Japan Trench of the 20th century, none of which attained M8. A predecessor may have occurred on July 13, 869, when the Sendai area was swept by a large tsunami that Japanese scientists have identified from written records and a sand sheet.

Continuing readjustments of stress and associated aftershocks are expected in the region of this earthquake. The exact location and timing of future aftershocks cannot be specified. Numbers of aftershocks will continue to be highest on and near to fault-segments on which rupture occurred at the time of the main-shock. The frequency of aftershocks will tend to decrease with elapsed time from the time of the main shock, but the general decrease of activity may be punctuated by episodes of higher aftershock activity. The risks of great earthquakes at locations far from northern Honshu are neither significantly higher nor significantly lower than before the March 11 main-shock. (USGS)

Featured image: Google Earth + USGS

None of this is very suprising, this region, known for over a century as the Dragon’s Triangle, is noted for both volcanic and fault instability. In fact Japanese Architects are consulted world wide for designing “earthquake resistant” buildings.