“Historic” Bering Sea Storm slamming Alaska coast with hurricane power

The historic Bering Sea storm everyone’s been talking about since Tuesday has begun to batter the coast of western Alaska, with the Bering Strait, Seward Peninsula, Norton Sound and Yukon Delta areas expected to take the brunt of it. Current forescasts expect the storm to continue through Wednesday and diminish by Thursday.

The NWS has analyzed the central surface pressure of the storm as of Wednesday night and found it at 944 millibars as it passed west of St. Lawrence Island. That pressure result is as low as a strong hurricane’s would be at lower latitudes.

The potentially historic ‘superstorm’… is making ‘landfall’ in Alaska today with a pressure equivalent to a Category 4 Hurricane reports AccuWeather.com.

There were that widespread power outages hit for a while overnight in Noma area, some cars went in the ditch, and roofs have been at least partially blown off several houses and water at the base of a lot of houses. Blizzard conditions were in effect at Nome from the middle of Tuesday evening to early Wednesday morning, but now visibility is up to one mile. The power was out for at least several hours overnight, and estimated winds gusted to as high as 61 mph.

Water has been reported at the base of a lot of low-lying houses in Nome, is spreading over the sea wall, and high seas and waves pushed some water into town. High tide overnight Wednesday is expected to be about 7-1/2 feet, and tides are expected to rise about 7 feet higher than normal tonight, which will bring total water level to about 8 feet, AlaskaDispatch reports.

Communities affected by the storm since Tuesday:

- Kivalina – Severe weather conditions are occurring now and will continue. Highest wind gust so far in Kivalina 72-73 mph.

- Point Hope – Wind speeds as high as 79 mph.

- Wales – Very strong winds overnight – highest gusts reached 89 mph.

- Teller – Maximum winds about 72 mph.

- St. Lawrence Island – Savoonga continues to be very windy, with maximums of 76-77 mph

- Gambell – Maximum winds near 70 mph.

- Eastern Norton Sound – Unalakleet has had maximum wind gusts about 68 mph.

- Golovin – Some peak winds in the upper 60s.

- Koyuk – Overflow along the beach, tide still rising.

- Shishmaref – Quite windy there but no damage or injuries. Some land lines are out.

- Elim – Water reported to be steadily rising overnight.

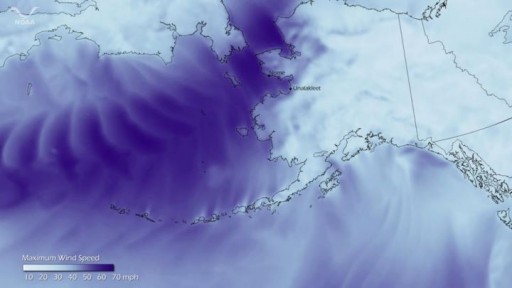

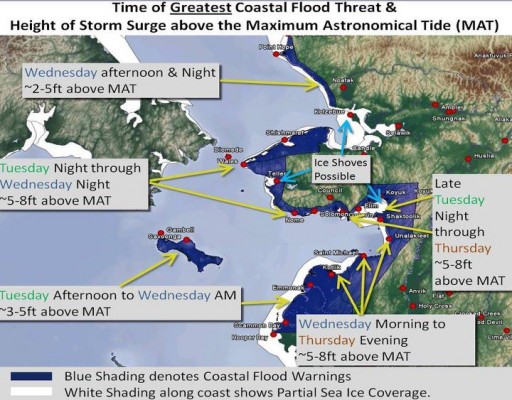

The Alaska Division of the Homeland Security and Emergency Management has posted a summary map on its Facebook page,with detailed information about flood danger, ice shoves, and expected flood surges across the threatened area. Here’s a satellite image / weather map from CIMSS.

Water is expected to rise about 2 more feet this evening in Nome, where water already has moved to the base of some buildings, National Weather Service forecasters told the Anchorage Daily News.

If you’re not an avid arctic-storm watcher, it’s hard to know where to turn for information about the storm’s progress. Here’s a quick guide to keeping up with the situation.

- The National Weather Service is obviously indispensable, but their site is difficult to navigate. This is the main page that you want to keep an eye on.

- The Department of Homeland Security also puts out a situation report on Alaska each day, which you can read here.

- Local and national news organizations are tracking the storm. Try the Fairbanks@newsminer, the Fairbanks paper, which has been keeping up a steady stream of tweets. TheAlaska Dispatch is another excellent local news outlet. KTUU is a good Anchorage television station to keep an eye on. And of course, the Anchorage Daily News is a standby.

- Newsminer also provides an excellent list of webcams through which you can watch the storm make landfall.

- The Twitter hashtag appears to be #AKstorm, though I’ve seen several variations. If you’d like a more curated feed of tweets, the Weather Channel put together a list of 13 people and news outlets to watch.

- FEMA is watching the situation, too.

Does the Bering Sea have hurricanes or just strong storms. If warn waters fuel tropical hurricanes, what fuels hurricanes in the Bering Seas?

Hurricanes form in warm waters. The warm water creates a high and low pressure, resulting in the air moving rapidly in a spinning motion. The warmer the water, the more strength it will have. When it usually reaches land, it dies within a matter or days due to the fact that little pressure is created on land. Sometimes very strong fluxes of thermal energy from the ocean to the atmosphere occur. Those large thermal fluxes come mainly from the very large temperature difference between the winter atmosphere and open ocean, which can often be around 20 deg C. However, the maximum simulated surface winds of about 90 km/hour were not as strong as the threshold for category one hurricanes of 118 km/hour. The dynamics of those storms (polar lows) are closer to a standard mid-latitude cyclone (known as baroclinic). The polar low then decayed after moving over land, which cuts off the supply of energy from the ocean. In winter the temperature difference between the atmosphere and ocean (and therefore potential for large energy fluxes) is large enough to support a genuine Arctic hurricane. Usually, polar lows never develop into mature hurricanes because there is simply not a large enough expanse of relatively warm ocean over the Arctic in winter. Hurricanes take of the order of five days to drift across the tropical Atlantic and slowly intensify, whereas most polar lows move over land or ice in one day. Polar lows last on average only a day or two. They can develop rapidly, reaching maximum strength within 12 to 24 hours of the time of formation. They often dissipate just as quickly, especially upon making landfall. In some instances several may exist in a region at the same time or develop in rapid succession. Typically several hundred kilometers in diameter, and often possessing strong winds, polar lows tend to form beneath cold upper-level troughs or lows when frigid arctic air flows southward over a warm body of water.